"I'm trying to pay attention to some of the new rhythms of life and how things have changed."

José Olivarez on family, craft, and trying to write a poem "that has the same energy as a Bad Bunny song"

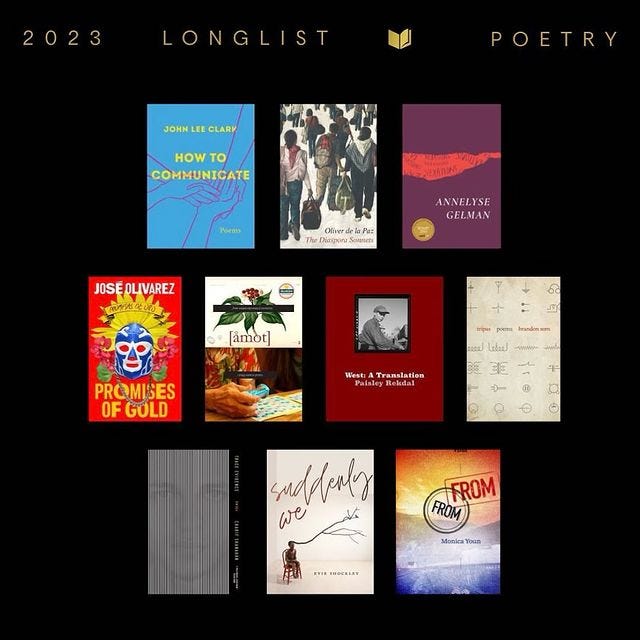

Y’all! In the week since we published the first part of our conversation with José Olivarez, he has been long-listed for the National Book Award’s prize in poetry! Huge congratulations to José!

In this second half of our conversation, we discuss José’s craft more broadly, his collaboration with photographer Antonio Salazar, and what’s on his horizon. If you missed the first part of our conversation with Jose, where we focus on his poem “Ars Poetica,” take a look:

ALIX DICK: Can you describe a bit how your identity shapes your work?

JOSÉ OLIVAREZ: Well, when you talk about identity, there's many layers to it. I try to write from the specificity of how a bunch of my different identities are kind of intersecting and overlapping at the same time. I think that there's a lot of richness to be found in the way that our identities help inform our perspective and sometimes provide a contradictory experience. So, one thing that I think grounds a lot of my work is not just being Chicano, but also being from a working-class family, being from a family that was formerly mixed status when my parents were undocumented. All of those very specific experiences helped ground my writing in not just details and voices and memories and language, but also in a particular texture that give it some of its uniqueness in the world of writing.

ANTERO GARCIA: How did your parents respond to you becoming a poet?

JO: When I started writing poems, my parents were confused. They were like, "What?" I think they expected that I would eventually stop writing poems. I went to Harvard supposedly to study government and become a lawyer. And ultimately, I did not enjoy those classes all that much. I just kept coming back to literature, and I found myself spending more time in the library studying poems and reading things that were not on my syllabus.

So, when I came home and I told them that I wanted to become a poet, they were super confused, and they were like, "Mijo, can't you be a poet on the side and still be a lawyer?" And then I think they were like, "All right, well just don't write too many family secrets." … and then they were like, "Don't be such a chismoso."

[laughs]

When I started to get published, I had a book party for my first book at the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, and my parents sat in the front row, and I think they were very proud and emotional. And afterwards, they introduced me to a bunch of cousins that I had never met before. So, I think now they're very proud, but I think it took them a while for them to see that it would actually work out okay for me.

AG: You needed the museum gala to get the credit.

JO: Yeah, exactly.

AG: Does your brother consider himself a published poet now?

JO: That's a good question. He started writing poems kind of on his own. I don't think he necessarily has aspirations to publish poems, but I think he views it as a valuable practice to get in touch with his feelings and kind of have a place to put some of the complicated emotions of what it means to be alive. He shows them to me sometimes, but I don't know if he considers himself a published poet. I mean, he is, I think whether or not he considers himself one, it's true. His poems are published in the book.

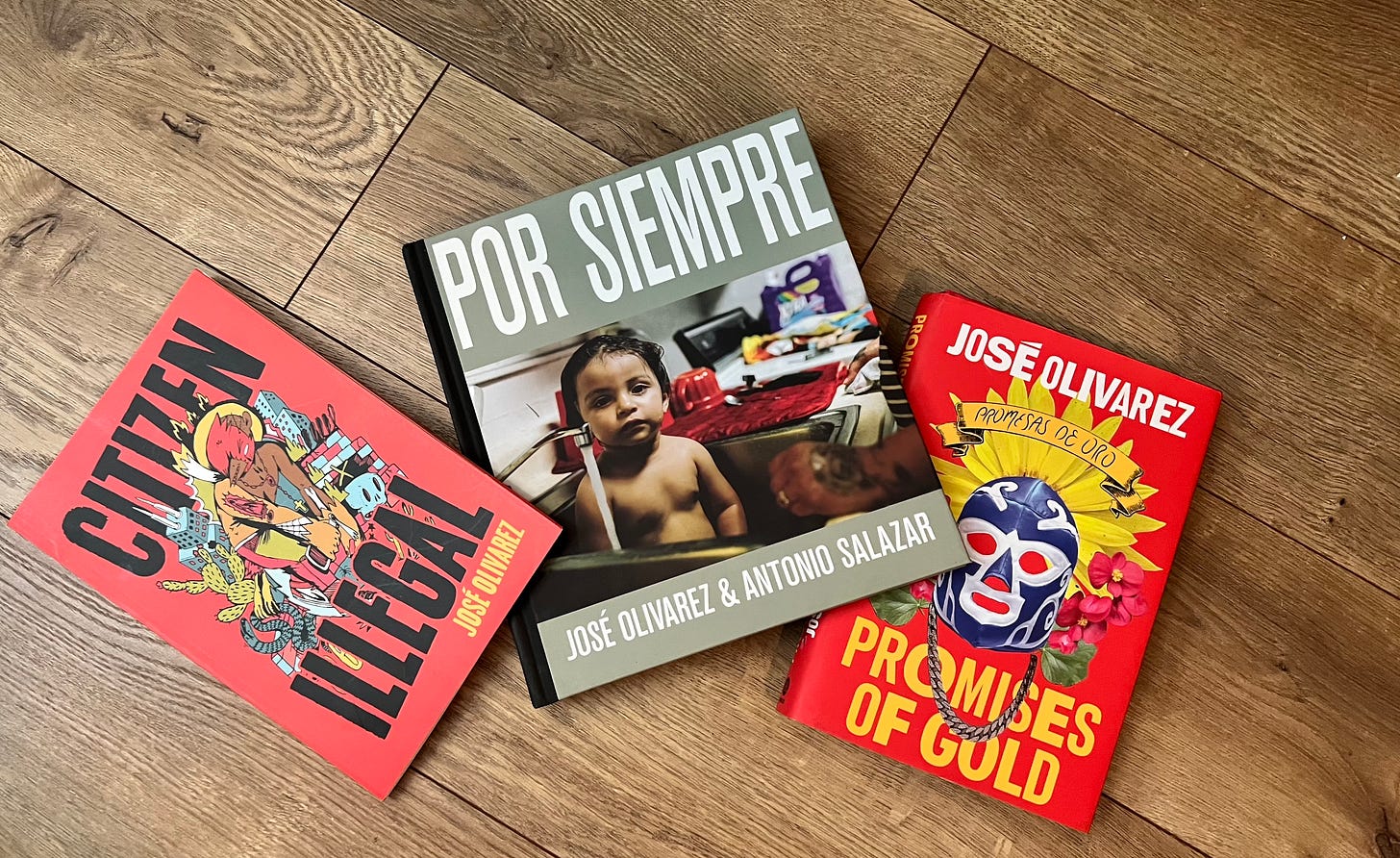

AD: I wanted to ask you about the process of writing Por Siempre. I love the concept of that book, by the way, everything about it is so beautiful.

JO: That makes me so happy. Por Siempre started when I visited Phoenix in 2018. The cover artist for my first book is an artist named Sentrock. And Sentrock is originally from Phoenix, Arizona and has spent the last probably 14, 15 years at this point, living in Chicago. So I knew Sentrock-I love his art. He has murals all over Chicago, so I would see it all the time. His signature character is a person wearing a bird mask. And to me, I felt that very deeply1.

Because at the end of the day, I think about my parents, I think about my family, and they were trying so hard to kind of transcend whatever their origins were, but at the end of the day, we're humans. We put on the mask of flight. We do our best to try and overcome, but we're still regular people who are going to make mistakes and who are going to lose sometimes. I love Sentrock's work.

I think about my parents, I think about my family, and they were trying so hard to kind of transcend whatever their origins were, but at the end of the day, we're humans. We put on the mask of flight.

When I got invited to go to Phoenix, we became friends over the process. Sentrock was like, "Oh, you got to connect with this person.” And one of the people that he connected me to was Tony. And so I went to Phoenix, and I didn't necessarily expect that Sentrock's friends would actually pull up on me and offer to take me around. But Tony pulled up on me and he was like, "Let me take you, not just to where the university is, but let me take you to the west side of Phoenix and the south side of Phoenix. Let me take you up to the mountain." We're cruising, and he's telling me about how different people get together and what happens in Phoenix. And he starts showing me his pictures. And I just thought they were so beautiful. I felt a real connection to one of the purposes that I see in his work: so many of those photos are very masculine and tough, but the photos are taken and treated with such tenderness.

It's so clear that as a photographer Tony loves the people and the community that he's taking photos of. And so for me, there was something that I really connected with about his process, about the photos themselves, and I think it's not too different from what I'm trying to accomplish as a poet.

AD: Oh, I love that. You created an amazing work together. What is inspiring you right now?

JO: In some ways, it's probably some of the same things that always inspire me… Music and, in particular, I've been trying to think about what a poem would look like that has the same energy as a Bad Bunny song. So, I’ve been thinking of what a Bad Bunny poem might sound like and feel like. And in particular, he has these almost grunts in his songs that feel so emotional. So what does that sound look like, how do you incorporate those kind of punctuations?

In addition to music, always my friends. My wife is very inspiring to me.

I’m trying to pay attention to some of the new rhythms. I'm married now, so trying to pay attention to some of the new rhythms of life and how things have changed and how they haven't changed.

AD: That's beautiful. Thank you for sharing that. What are you working on right now?

JO: Right now, I'm working on a novel that I have imagined as a reverse migration novel. It begins in Chicago with two friends who decide that basically their families were wrong to migrate north and decide that they must migrate south in order to find the answers that they're looking for. What I'm hoping for is to kind of flip the traditional narrative that the north represents the final answer, and that the north is where all the answers are, and to see what comes up when you have people go through a different kind of migration than what is usually expected.

Propina

We want to thank José and congratulate him one more time! If you haven’t read any of his books, why not start with (again for the people in the back) his National Book Award’s long-listed work (!), Promises of Gold (and check out our conversation about his poem, “Ars Poetica” here).

(BTW, José isn’t the only poet La Cuenta’s been speaking with lately … stay tuned!)

In the meantime, we are thrilled that staff writer, Christián Pena joined Anna Lekas Miller on Instagram Live for a powerful conversation this week. If you missed it, take a look:

We’ll see you next week!

Fun fact: isn’t the first interviewee to give a shout out to Sentrock. Check out our conversation with Silvia Rodriguez Vega!