"Who does it serve to write stories of trauma for the sake of spectacle for a white consumer?"

José Olivarez discusses his poem "Ars Poetica"

Reflecting on the irksome responsibilities he shouldered as a poet while studying at Harvard, José Olivarez explained, “If I wrote a poem about the trees in New England during the fall and how beautiful they were, my classmates would read that poem and they would start to say things like, ‘The trees shedding their leaves is a metaphor for how assimilation works …’”

So goes the tensions that Olivarez tackles head-on in his three collections of poetry. We’ve been fans of Olivarez’s poetry since first digging into his 2018 debut, Citizen Illegal. This week, we share our conversation focusing on José’s poem “Ars Poetica” and its themes as they relate to immigration and identity. With his permission, we are sharing the poem in its entirety below, as well as the Spanish translation completed by David Ruano González.

ALIX DICK: In the middle of “Ars Poetica,” you write, “My work: to do more than reproduce toxic stories I inherited & learned.” Did you see this as the driving goal when you wrote this poem?

JOSÉ OLIVAREZ: I think so. The poem surfaced for me when I was applying for a poetry grant. The question that they asked was, “In 150 words, tell us about your poetry.” And this is a grant that I had applied for seven or eight times. You're eligible for this grant between the ages of 21 and 31. I always struggle with that question. I don't really know what I could say that the poems don't already kind of say for themselves. I wanted to try to answer that question without really giving an answer.

And so, I kind of came up with this format where the questions led to more questions. The poem uses a lot of colons, right? To me, the colon kind of signifies trying to get to the next question as opposed to trying to come up with specific answers. So the poem was a way to articulate that goal. In the world of diversity, enrichment and inclusion, DEI, I think there's this false understanding that all "diverse stories" have a positive value or that they're all good contributions because they're diverse. I think a Mexican story that is re-inscribing some of the harms that we experienced is not necessarily a positive one, even if it is very Mexican. And so, for me, “Ars Poetica” is an attempt to say, I hope to be doing more than just re-inscribing some of that toxicity that I grew up around and know very intimately.

ANTERO GARCIA: Did you get the grant?

JO: I did.

AD: Oh, that's amazing! When you wrote “Ars Poetica,” who did you hope would read it?

JO: It’s an ars poetica, which are kind of mission statements for poetry. In that sense, I think it's probably most useful to other writers, whether they're creative writers or not. But I hope it's useful to anyone that finds a spark in it, that finds their own sense of purpose in the poem.

AG: As I read this, I was thinking about an ars poetica as a grand, Western poetic practice. And this poem opens with OG white linguists, Merriam and Webster, and ends with Susan Sontag. You've got these authoritative white voices speaking alongside reflections on Mexican family and Mexican identity. How do these factors play out to you in this poem?

JO: I hadn't thought about beginning and ending with these two kinds of white voices. For me, when I was writing the poem, it made sense to begin with the kind of dictionary definition of migration, which immediately posed problems to me. It tries to articulate migration as a definitive process, one with a definitive beginning and a definitive ending. In my experience, it's a lot more complicated than that. And then the same thing with Susan Sontag. She is someone who I had been reading during this summer that I was working on this set of poems, not specifically for the grant, but working on my writing. In particular, she has a long essay about violence and images and the reproduction of violent images and whether they can be useful. And so I was thinking a lot about, who does it serve to write stories where Mexicans die in the process of crossing borders or who does it serve to write stories of trauma for the sake of spectacle for a white consumer?

I was thinking a lot about, who does it serve to write stories where Mexicans die in the process of crossing borders or who does it serve to write stories of trauma for the sake of spectacle for a white consumer?

I kind of felt a bit of discomfort with the proposition of what I saw as one of the expectations for Mexican writers, which was to articulate a type of Mexican pain and make it consumable and honorable for white audiences--for them to be able to read this story and come away and feel good about themselves and say, "Well, now I understand the suffering of immigrants in the United States." That’s kind of where those two voices came from. In thinking about your question, honestly, it makes me feel a little bit of discomfort in beginning and ending it that way.

AG: Oh no!

JO: It makes me wonder. I think it's worth pointing out, and it does give me a little bit of discomfort.

AG: What’s beautiful about the poem is that it doesn’t end with this white voice… it remains open ended for the reader.

AD: Have you felt the pressure of avoiding the kinds of narratives that people expect you to write as a “Mexican poet”? As a writer that’s “dislocated by capitalism,” is there a pressure for you every time you put your pen to page?

JO: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think there was, and maybe there still is, but the pressure is kind of twofold. One is that reading works in the United States, we read for identity as much as we read what's actually on the page. And so one of the things that I found with publishing my first book, was that there's a poem about cheese fries in that book, there's love poems in that book. But I would visit classrooms and the teachers would ask me how cheese fries relates to the immigrant experience.

And I had this experience when I was a student, where I tell this story, but I went to college at Harvard, and if I wrote a poem about the trees in New England during the fall and how beautiful they were, my classmates would read that poem and they would start to say things like, "The trees shedding their leaves is a metaphor for how assimilation works and how the tree must adapt to the harsh New England weather the way that Chicano students at the university must adapt to the harsh climate."

I would visit classrooms and the teachers would ask me how cheese fries relates to the immigrant experience.

They would start to make up all of these associations, and I'd be like, “No, it's just the trees are really beautiful, and here's a poem about the trees.” So part of it is understanding that it kind of doesn't matter what we write as Chicano poets, Mexican-American poets, migrant poets. Our writing will always be read as a metaphor for the migrant experience. And if we understand that, how can we subvert those experiences and maybe have fun with those expectations?

AD: You could write a whole cheese fries collection of poems, but people will only see it as the immigrant experience or migrant experience.

JO: Yeah, exactly. “The processed cheese, what does that represent? Is that how capitalism and United States culture kills us slowly, even though we might enjoy parts of it.” They'll just make things up.

AG: Well, we look forward to your next collection, Velveeta of the Heart.

[laughs]

JO: Love it.

AG: In the acknowledgements of Promises of Gold, you write, “Poetry is communal. I might start the poem, but you finish it.” And with “Ars Poetica,” ending with an open colon, how could you imagine a world that finishes the poem in a way that might be fulfilling?

JO: I mean, for me, it begins with transforming the material circumstances of the people that live here. But I think that leads me to also considering the ways that the empire of the United States affects people who do not live here. And so, I think for me, it just requires so many different transformations. But I guess what I'm really thinking about is, I fundamentally believe that people deserve safety. They deserve food and shelter and go from there. That's the beginning of an answer to me.

Propina

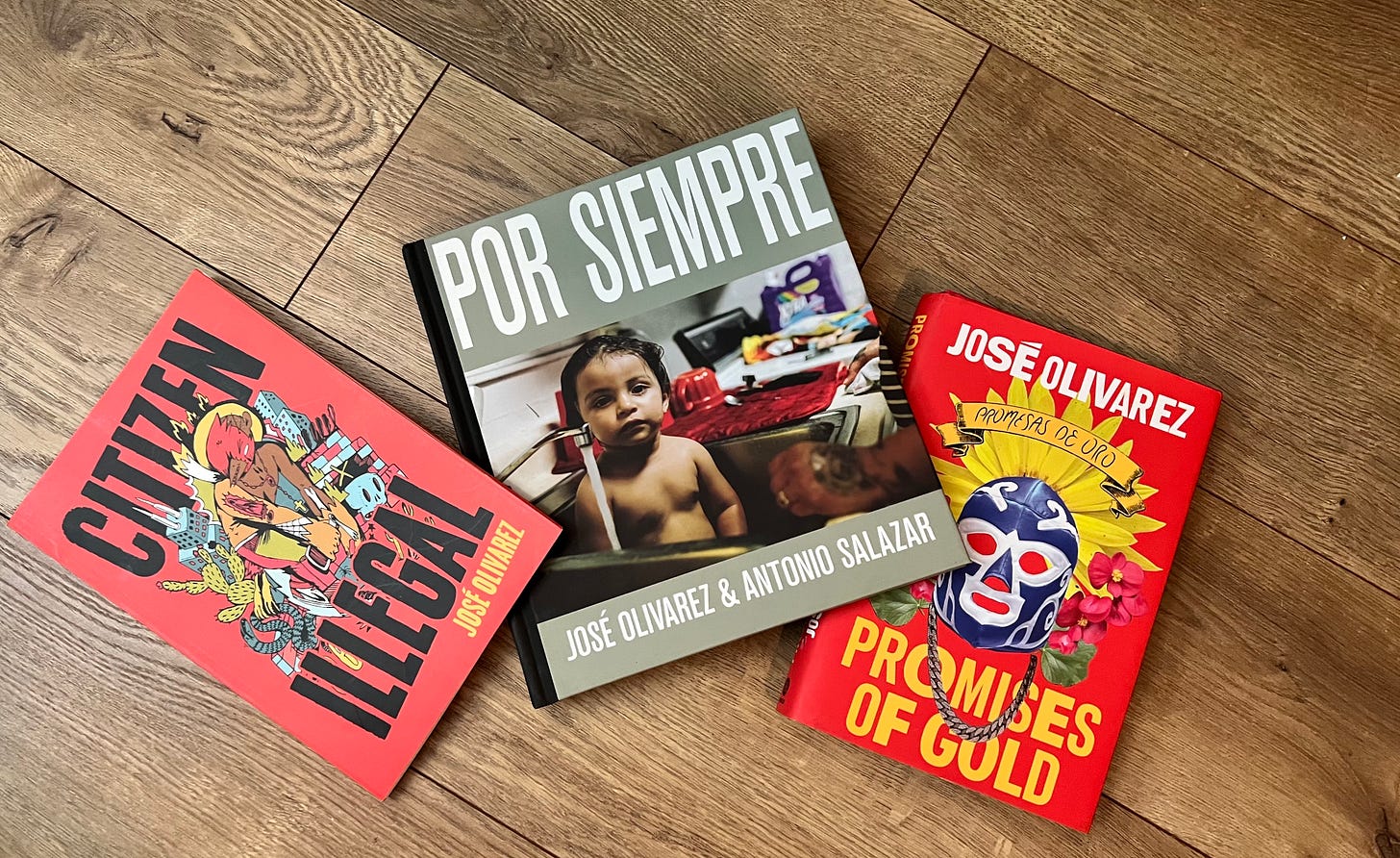

We’ll share the second half of our conversation with José next week, focusing on his approach to writing and the work that is on his horizon. In the meantime, if you have not spent time with any of his work, we encourage readers to take a look at his three collections of poetry:

Citizen Illegal - José’s powerful, funny, moving debut collection.

Promises of Gold - José’s follow-up to Citizen Illega. This collection includes “Ars Poetica.”

Por Siempre – José’s most recent collection is a collaboration with Phoenix-based photographer, Antonio Salazar. It’s a powerful collection and we dive into the origins of this project in our conversation next week.

We’ll see you next week!