"I Am Not the Survival. I Am the Victory."

Yesika Salgado on the privilege of writing and how "this country broke [her] father.”

We have come to the third and final part of our interview with Yesika Salgado, a truly special and inspiring project to have been able to work on and share. (If you missed earlier portions of the interview, part one is here and part two is here.) I am very grateful for the safe space that Alix and Antero have created here on La Cuenta. It’s beautiful to not only be able to write the stories I never thought I could but to be in community with others who have shared their stories with us and allowed us to bring them here to La Cuenta.1

This title for part three changed several times, at some point it was a very morbid title—something that Yesika shared with me toward the end of our conversation—but then I remembered an interview that Alix and Antero did with Juanita Monsalve the Creative Director for United We Dream. In fact, I restacked a quote that I carry with me since that day. Juanita said, “I genuinely think that folks who I know who have experienced being undocumented, their day-to-day is not sad. They’re very happy people. Our people always find joy.” I didn’t want to end the interview with Yesika with something sad, because although there are moments of sadness, she is right, we know how to find joy. Joy is a radical act. Yesika Salgado has written poetry of her family’s struggle, poetry about love and finding herself as a woman, and she is full of joy and shares it with others.

In the end, I chose a title using some of the words from Yesika’s poem “Diaspora Writes to Her New Home” where she wrote, “I am not the survival. I came after. I am the victory. A boastful flag.” because I want this for all of us. I want this for my children, for our children, for us to no longer be the survival but a victory, a boastful flag.

Welcome to part three: “I Am Not the Survival. I Am the Victory.”

CHRISTIÁN PEÑA: Okay I’m going to take a moment and fangirl for a second because you are one of my favorite poets, haha. About a year ago there was a poem that you shared on Instagram, without a title, that I connected with very deeply. It’s the one that starts with “You sweet love awake at 1:00 a.m.”

YESIKA SALGADO: Oh yes, that one doesn’t have title.

CP: I was up late, scrolling through my phone, just like in that poem, battling with some internal demons at like two in the morning and that line “Go to sleep baby” felt so warm and reassuring when I read it.

YS: Aw, I’m glad. And the thing is, that those poems, those things — I don’t write them and be like “I’m going to help all the girls that can’t go to sleep.” You know haha?

CP: You write them for you, right?

YS: Yeah, literally it’s just like, “Babe it’s three in the morning. You need to go to sleep, you need to surrender this stuff.” And when I write them, I am all heart. There is no method to what I do. It’s just instinct, sometimes I just feel like, “I should share that poem today.” I feel compelled to share it whether it’s because I am going through something or I come across something. And I share it and sometimes it’s the day that somebody needs it.

When I write them, I am all heart. There is no method to what I do. It’s just instinct.

But, I am really lucky that I have a job and a career where I get to honor my instincts and honor my heart on a regular basis. And I understand the privilege of that. And a lot of my privilege comes from me not being an undocumented person because I don’t have to worry about my safety, my legal, and my physical safety.

In some ways, my identity is very privileged because I am also a cis straight woman. So I am not writing about queer love and risk that pushback. But I am a fat woman, and that’s why I write about sex and love a lot, because I used to think that as a fat girl I couldn’t talk about those things —I thought who would believe me that I was having sex or that somebody was in love with me? So if I felt like that as a teenager, I know there are other people that feel like that.

CP: That’s beautiful and I think that your poetry is definitely doing that because it has comforted me over the years.

YS: Thank you.

CP: I have one more question for you before we go. La Cuenta is named after the idea of sending a bill to the United States for the costs of being undocumented. Based on your family’s experience as refugees and living undocumented, what would you put on that bill?

YS: If I was charging the United States for my parents’ cost of living — it's so much more than the material. I think of my father, and I think of what my cousin’s wife once said, “This country broke your father.” And I feel like that’s very true. My father lived comfortably in El Salvador, his family owned a lot of land and he was going to a nice college where he was planning on studying medicine — all of a sudden he had to walk away from that because of the war. He was forced to leave to another country to seek refuge where he ended up as an underpaid service worker and wasn’t qualified for much else. That made him very resentful, very frustrated, very angry. And that meant that I had a very resentful, very angry, frustrated, sad and depressed father. They didn’t have access to mental health support and I would bill them for that. I would bill them for my father, for my 39 years of therapy or however long — counting the years when he landed here. I would bill them for the trauma of the civil war that caused the displacement of so many people in my family.

[My father] was forced to leave to another country to seek refuge where he ended up as an underpaid service worker and wasn’t qualified for much else. That made him very resentful, very frustrated, very angry.

I would bill them for what my mother’s salary should have been all the years that she worked as a live-in housekeeper. Working her ass off to keep other people’s houses clean while her daughters were being babysat by other people. And I would charge them for the scarcity mindset that my parents’ had, and the choice that it took away from us because they weren’t only supporting the family here, but the were also supporting the family they left behind. And as young girls, you don’t understand that. All you know is that you want a Barbie but you can’t have that Barbie that you want.

It’s so much more than the tangible things that I feel my parents are owed. I think mostly it’s the sacrifices that they had to make, that often get romanticized, but that are real and painful.

CP: The cost is far too great for numbers, it’s lives that could have been lived with less struggle and pain.

YS: It’s the way that it drained their lives. I don’t care about my life in the sense of what I feel this country owes me. I don’t care about that. I care about what it took from my parents. Because at the end of the day I get to live my dream, they did not.

CP: Do you feel like in some way that is why you have written so much about your family and the things they have endured since their leaving El Salvador?

YS: Yes, but I also understand my privilege as a citizen and how I have to be careful in my telling of my family’s stories. I used to always want to write about their migration, I wanted to document it because I felt that as I writer it was my job to document my parent’s story. The older I got, the more I realized — in the last ten years—that it’s not my story to tell. And that’s why in Hermosa the first poem in the book is “Diaspora Writes to Her New Home”. I wrote, “I am not the survival. I came after. I am the victory. A boastful flag.” I was born here in the United States and I have made a life for myself as a writer. But I have to keep in mind that I am extremely privileged to be able to write things with impunity, to not be worried about writing about someone being undocumented and running that risk.

Propina

[Note: the final exchange from Yesika serves as the propina for this week.]

CP: Thank you for sharing yourself with us before we go, can you tell us of any upcoming projects that you would like to tell us about?

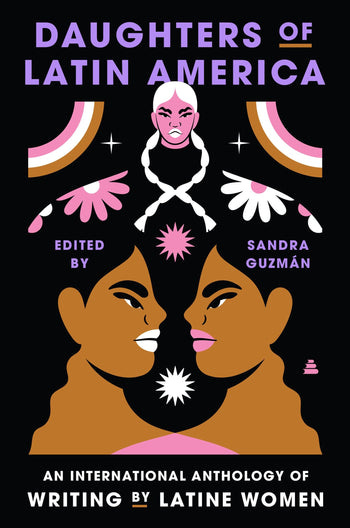

YS: I have been working on a fourth book for a long time. So we will see when she shows up in the world. Her name is Mentirosa and she focuses a lot on the years that I spent catfishing on the internet. It talks about what people do when they feel unlovable—especially women—and how the world takes our bodies from us. In it I am processing my girlhood and how I spent so much of that time enduring the criticisms against my body. Oh and I had a poem published in Daughters of Latin America an amazing, amazing anthology.