"Qué Hermosura"

Yesika Salgado reflects on responsibility as a writer and the inadequacies of translation.

Someone once said to me, “Who gets to tell these stories?” during a discussion about personal narratives. It’s a question I ask myself often when I sit down to write and a story has found its way out of me, a story that makes me uncomfortable, one where I worry about its impact and who may feel wronged in me writing it.

So who gets to tell these stories and how does language change the way we move through a story teeming to find its way out of us? In the first part of our interview I asked Yesika Salgado about how she decides when and how to write in Spanish, her response captured something I have felt but could not put words to: “Spanish is my home.” When another language feels like home, how do we express that home, that emotion, that often cannot be translated in our storytelling or our poetry?

I loved this conversation with Yesika and to be able to listen to her talk about the complexity of loving someone with an addiction, bearing witness to their pain, and loving them in all that they are and how writing offers us the safe space to make sense of that which emotions often make it difficult to make sense of.

Welcome to part two: “Qué Hermosura”

Translation: not beauty, not precious but a marvel to be witnessed.

CHRISTIÁN PEÑA: Do you think it's possible to translate certain Spanish words into English while preserving the cultural nuances and deeper meanings?

YESIKA SALGADO: I’m not sure if there is a way for them to translate the same. Like there is hermosura right? Hermosura is more than beautiful — it’s not precious or preciosa. So you’re like how do you explain hermosura or when someone says to you “Qué hermosura.”

CP: What does that mean for you?

YS: For me, when it was used towards me, my dad would use it like “¡Hermosura!” He would use it in marvel. Considering me this beautiful marvel. My dad would call us hermosura but it wasn’t a word he used often, but it was a word that he used to describe us usually when we were all dressed up and we were going out. It was his way of saying, “You look beautiful.” Kind of machista huh? haha.

And then las señoras in El Salvador would call me that because I’m this fat girl — what most people would see as a negative thing and ask “why are you fat?” the Señoras would say “Hermosura”, this big girl, that there is so much surplus in your life that you’re fat — that this could be possible. That someone can be fat because there is an abundance. They would smack my arm lovingly and with wonder say “¡Qué hermosura!” And how do you explain that in English?

They would smack my arm lovingly and with wonder say “¡Qué hermosura!” And how do you explain that in English?

CP: That’s beautiful, and even as I listen to you explain what it means to you its hard to find a better description other than the way you articulated it — a marvel, like you are a marvel and its a marvel to be able to witness this person. Is that why you chose Hermosa as the title for your book?

YS: So when I was writing Hermosa I was having a really hard time with it. There was no direction, no concept, I just had all of these poems and I was complaining about this to everybody. When you’re working on a project — everybody knows you’re working on a project.

A good friend of mine, Gabby Rivera, who’s also a writer she wrote, Juliet Takes a Breath and the America Chavez comics, was in town working on something. We had lunch, went to go get pupusas and after we were done eating she said, “Okay, I’m here in LA to work, so let’s work.” and I was thrown off I was like, “What are you talking about?” and she said, “Your book, where are you stuck?”

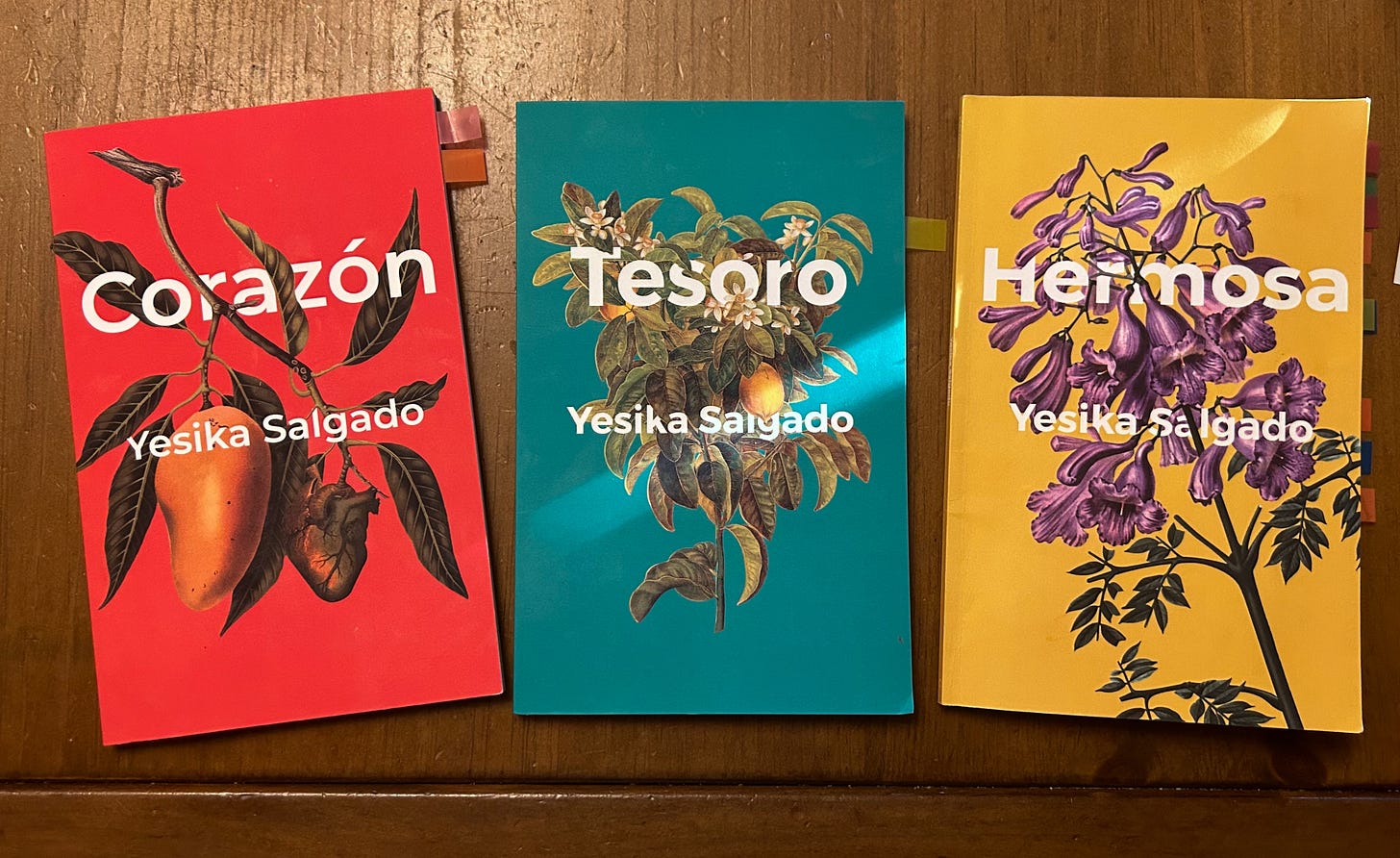

So I start crying and I’m telling her what I’m feeling and she goes, “You know what Yesika, as a fan, can I tell you something? As a fan of you and your work, I have yet to see this Yesika in your work — confident, long nails and jewelry on Yesika. And it finally clicked for me. I already knew that the book was going to be named Hermosa when I was working on it, but the meaning of the title changed for me. At first, it was just a nod to Corazón and Tesoro which are also things that my dad would call me and my sisters. Hermosa changed for me in that it became a love letter to LA and to myself, this marvel of what the city is and the woman that I am within it. The book became an exploration of this larger story of how my parent’s love and life affect the woman that I became and who I was becoming.

Hermosa changed for me in that it became a love letter to LA and to myself, this marvel of what the city is and the woman that I am within it.

CP: Did Hermosa make you feel as though you were uncovering another aspect of your identity as a writer?

YS: When I was writing Corazon and Tesoro I had so much to prove to the world so writing Hermosa it felt like I was catching up to everything I had accomplished in the last few years. In other words it wasn’t the book that I was writing to convince people that I was a writer anymore — it was the book that I was writing because I am a writer.

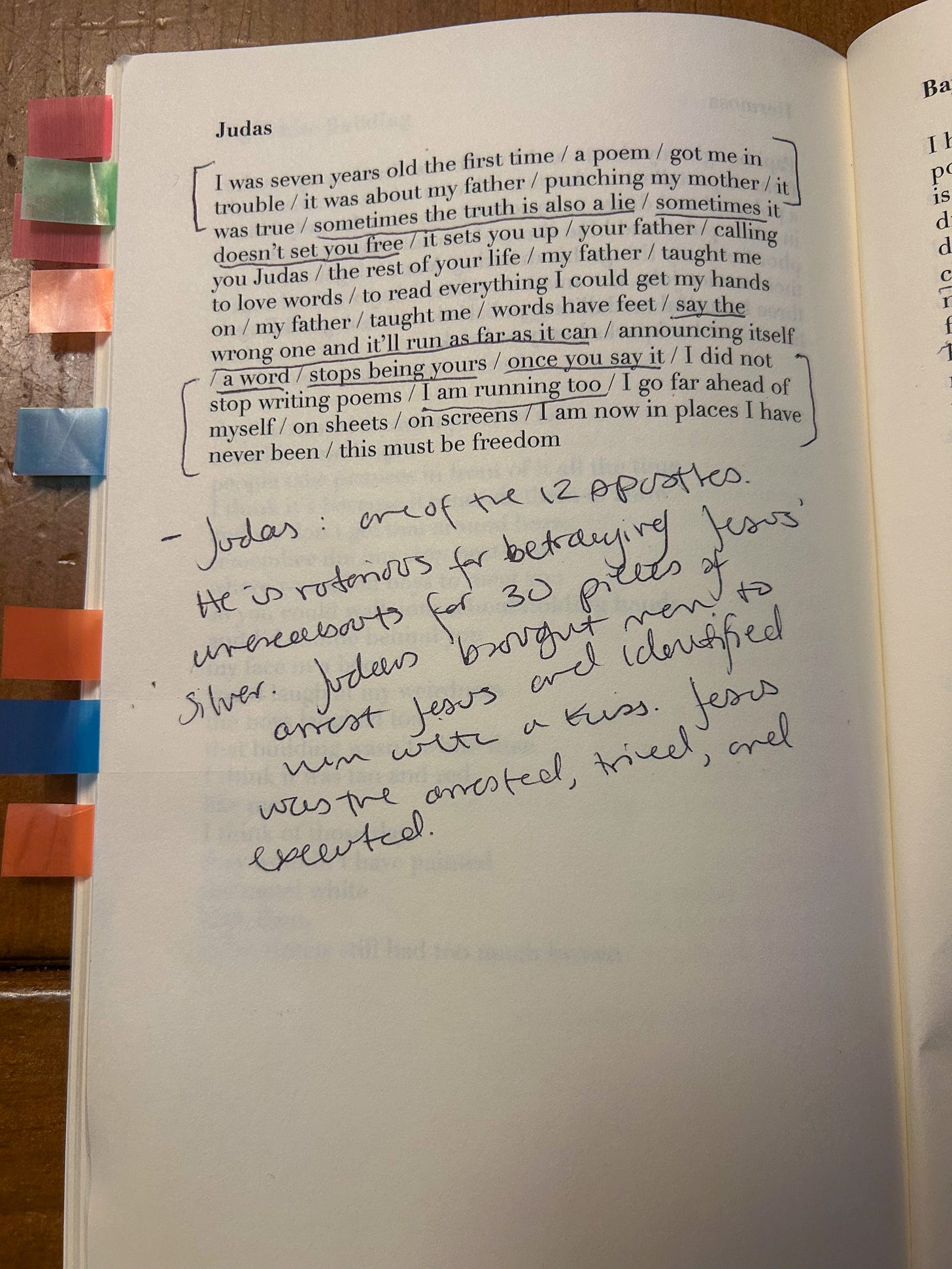

CP: I feel that when I read Hermosa. How do you make decisions about what to share? For example in your poem Judas you write about a poem that you shared when you were seven years old about your father punching your mother and that it got you in trouble. How did that moment influence your choices in revealing personal narratives?

YS: Well, my father passed away, my mother doesn’t read my work so there’s a little bit of freedom in that, but my sisters read my work so I do always worry about my sisters. When my father was alive, I wrote to make sense of a lot of things and I had a lot of internal things going on as well as a lot of external stuff going on. I always come to poetry to make sense of things, to write things down. Some of the stuff that I was writing about my family did not sit well with my sisters — it would really piss them off. And I think throughout the years, especially after our dad got sick and passed away due to his alcoholism, with how much we miss and love him we began to accept the complexities of him. Now as adults they read my work and they love how I honor him but they also understand the difficult things.

Every now and then, when I write a poem that mentions a lot of my mom’s personal life, I’ll translate it to her and explain it to her. I don’t think she understands how many people read this. I’ll ask her, “Are you fine with it being in a book or are you fine with me reading it on stage?” And she doesn't really care.

CP: I feel like we learned to keep these stories to ourselves in order to preserve our families, our culture and community and I always feel very comforted and empowered by writers who choose to tell them anyway.

YS: I think the writer’s job. Our job is to tell the story. And it will make some people uncomfortable because they are not ready to see the story for what it really is or any of that. So, sometimes when someone pushes back, you just have to let them sit in it. My sisters used to really not like my poems about my dad’s alcoholism, but I still wrote them. I still share them. Because at the same time it removes the shame for the families. I was so ashamed of having an alcoholic father. And sharing and writing about it has always allowed me to find that other people relate, other people who have experienced similar things.

In high school I read a poem at an assembly that I wrote about my dad and he was there at that assembly and that was hard for him to have to sit in the audience and hear it. But I had to make sense of it.

CP: I think that one of the things that I am still learning to do is how to tell the story in a way that allows me to make sense of it and also allows others to make sense of their story within my own. To create the sort of space of safe self-reflection the way your poetry offers us that space and has offered me that space.

Propina

We are grateful to Yesika for sharing her powerful words with us and—especially—to Christián Peña for bringing her full and vulnerable self to this interview and its introduction next week.

If you have not had a chance to read Yesika’s poetry, all of her books are powerful. Check them out here.

Join us for the third part of our conversation with Yesika Salgado next week.

What a beautiful read. It makes me want to connect with my language more- just reflecting on how much emotional meaning and memories a single word can have, it changes everything.