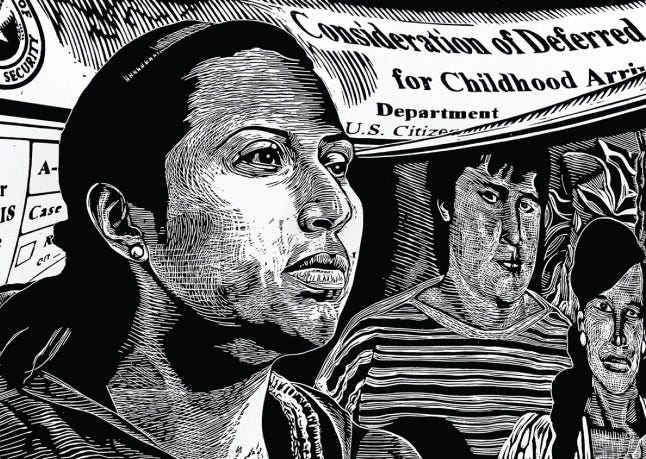

The Costs of Generation 1.5 - “Ni de aquí, ni de allá”

"It doesn’t matter how many degrees you get … there is no job for me."

“They say you can accomplish whatever you want or set your mind to, but they don't say that it's just for some.”

“I don't belong here because I don’t have my papers, so it's kind of like I’m in limbo.”

Brought to the U.S. at a very young age, the 1.5 generation of undocumented youth appear to be like any other American child, however, their undocumented status becomes a factor looming over every single one of their decisions.

“Ni de aquí, ni de allá”- from neither here, nor there

The “1.5 generation” is a term coined by academics to describe people who immigrated to the U.S. as children. Having spent most of their developmental years here, this generation faces a multitude of legal barriers. Immigration policies intended to discourage immigration make the 1.5 generation particularly susceptible to socioeconomic vulnerabilities as they transition into adulthood.

The thing is, the 1.5 generation are practically indiscernible from their “legal” counterparts. They grow up in the same communities, the same subcultures, and the same school environments as their peers, interacting constantly. Their “legal” counterparts are their friends, their teachers, their neighbors. (You, reading this, are probably their friends, their teachers, their neighbors.)

K-12 schooling environments bridge the constant movement between cultures for many of these young people.1 Unlike many older immigrants, the 1.5 generation are in settings where they could integrate and assimilate into their surroundings with less difficulty.

The thing is, the 1.5 generation are practically indiscernible from their “legal” counterparts. They grow up in the same communities, the same subcultures, and the same school environments as their peers, interacting constantly.

Undocumented youth grasp very early on the seemingly radical notion that citizenship is merely a set of papers— that’s it.

Existing as Actors to the World

Some individuals from the 1.5 generation may learn of their undocumented status at a young age. Others, often brought to the U.S. as babies or toddlers, go through their K-12 education oblivious of their legal status. As they grow up, the limitations accompanying an undocumented status begin presenting themselves. Undocumented youth become “othered” by their lack of legal status, facing exclusion from forms of social engagement some might consider trivial. The friends they’ve navigated their adolescence with with begin driving, working, and enrolling in college, touching on the milestones of their teenage years. Non-residents cannot get a driving license in most states, without a working permit they are not able to work, and all undocumented youth without DACA are ineligible for federal financial aid to fund their studies. While they see everyone growing and moving into the next chapter of their lives, many of this generation remain in a path of uncertainty for something they are unable to control.2 Socially excluded, undocumented individuals are forced to exist in a hidden dimension of social reality where they exist physically, but not legally.

The fear of being discovered soon follows. It drives them to exist simultaneously inside their bodies and as actors to the world. As soon as children learn of the violent practice of deportation, it is a fixating concern for themselves and for their families. William Perez, a Salvadorian immigrant and professor in the School of Education at Loyola Marymount University, interviewed undocumented high school students, community college and university students, college graduates, and formerly undocumented college graduates. His book We ARE Americans demonstrates the stressful experience of contradictory feelings of acceptance/belonging and rejection/isolation the 1.5 generation face.3 We opened this week's entry with statements from high school students featured in Perez's book.

Similarly, interviews with college students illuminate how undocumented youth internalize external barriers:

“The biggest disappointment is knowing there is no light at the end of the tunnel. Knowing that it doesn’t matter how many degrees you get, it doesn’t matter… there is no job for me.”

“I didn’t ask for my situation. I feel like it’s a punishment.”

“It’s like a wound that never heals that you learn to deal with.”

Exposure to chronic stress is especially harmful for adolescents.4 The mental struggle endured by undocumented youth often goes undiscussed. It is the invisible barrier that hinders their ability to pursue their dreams, augmented by legal barriers that affect the pursuit of their goals. While policies like DACA provide temporary relief from socioeconomic exclusion, DACA is merely a band-aid fix to a socially- and politically-constructed problem. We must advocate for a path to citizenship for all.

Propina

We feature quotes from William Perez’s book We ARE Americans in this issue. There is not enough space to discuss the complexities and implications born from the illegalization of our community in just one week’s post. We encourage you to check out Perez’s book to learn more about our experiences.

Pérez, William, et al. “‘Cursed and Blessed’: Examining the Socioemotional and Academic Experiences of Undocumented Latina and Latino College Students.” New Directions for Student Services, vol. 2010, no. 131, 2010, pp. 35–51.

Diaz-Strong, D., Gómez, C., Luna-Duarte, M. E., & Meiners, E. R. (2011). Purged: Undocumented Students, Financial Aid Policies, and Access to Higher Education. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education,10(2), 107-119.

Perez, William. We ARE Americans: Undocumented Students Pursuing the American Dream. Stylus, 2009.

Gonzales, R. G., Suárez-Orozco, C., & Dedios-Sanguineti, M. C. (2013). No Place to Belong. American Behavioral Scientist,57(8), 1174-1199.