“When our movements are siloed, we have wins in one arena that could end up as losses for some other community.”

Silky Shah on abolition, immigrant rights, and unbuilding walls

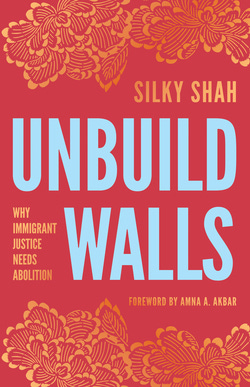

As soon as we picked up Silky Shah’s recent book, Unbuild Walls: Why Immigrant Justice Needs Abolition, we knew its empathetic vision of organizing and human rights was central to the values that drive La Cuenta. Discussing the professional pathways that led her to write her book, Silky reflected on her journey as an organizer and activist for more tha 20 years, in the wake of 9/11--“a catalyst moment.”

In addition to writing Unbuild Walls, Silky is the director of Detention Watch Network. In this first part of our conversation, co-conducted by Rita Kamani-Renedo, Silky describes the necessary links between abolition and immigrant rights.

RITA KAMANI-RENEDO: Can you describe the process of writing Unbuild Walls and why you chose to write it?

SILKY SHAH: In so many ways, the desire to write the book emerged out of the ways that I saw things shifting once Biden came into office. I had started working with DWN [Detention Watch Network] six weeks after Obama came into office, so there were so many lessons learned during that period. Detention Watch Network is a national coalition building power to abolish immigrant detention in the US, we've been around since 1997. There's just been a lot of changes in policy over time. We witnessed so much and saw the network and stances of organizations shift.

But especially in that moment of 2020, we were seeing where we could go with our demands and the space that was opened up because a broader conversation on abolition was happening. It was so powerful to see what was possible in that moment, so I wanted to really hold onto that and not lose sight of it, especially as Biden came into office. There were some really immediate, incredible things that happened right when Biden was inaugurated, and then it quickly waned and I saw shifts in the movement. And even with our team, with my colleagues at Detention Watch Network, I think for those of them who had done a lot of work in the Trump era, when people were really engaged and really paying attention, as well as for those of us who had worked under the Obama era where there was this perception that the president was pro-immigrant, I think we were a little bit more prepared for how much more work it was going to be for us to make the case.

There were some really immediate, incredible things that happened right when Biden was inaugurated, and then it quickly waned and I saw shifts in the movement.

So, there was just all these lessons learned: how the reformist approach really hurt us during the Obama era, how we were able to push beyond some of the underlying frameworks during the Trump era, how abolition really helped both guide us and open up space for our demands. All of that was percolating for me, and I was like, "Okay. Maybe there's something to say about this." So, that turned into the book proposal.

Initially, Cristina Jiménez, who was one of the founders of United We Dream, actually had solicited me to write a piece for The Forge, that turned into a piece about making the case around abolition for the immigrant justice movement.

ANTERO GARCIA: Can you describe your personal history coming into movement work?

SS: I grew up in Houston, Texas, which is an immigrant city in every single way. So, that was very normalized for me growing up, and I had friends who were undocumented and had just some perception of these things. 9/11 happened when I was 20. And I think, like many people who were young adults during this period of time who are brown, who are South Asian, or Arab, or Muslim, I was already kind of an activist on campus. I was at the University of Texas at Austin and was learning about different things. But 9/11 was sort of this moment of really both understanding the way the criminal legal system operated and then, all of a sudden, there was this extreme targeting of Muslims and Islamophobia. In national security frameworks that really informed the domestic war on terror that operated through the criminal legal system. So, I was starting to learn about that, and I was a student activist and I ended up working with one of the groups that had been pushing this in the university. I did divestment campaigns around private prisons. What we were seeing in Texas was essentially this post 9/11 prison boom. And even though I was considered a criminal justice advocate, all the prisons I was fighting were for immigrants. So, there was this tension where we were siloed between immigrant rights and criminal justice., but a lot of the work I was doing was actually at that intersection.

9/11 was sort of this moment of really both understanding the way the criminal legal system operated and then, all of a sudden, there was this extreme targeting of Muslims and Islamophobia.

I ended up learning about Detention Watch Network in 2005 and became a member. In so many ways, it was a very isolating period of time working on these issues. And most people didn't know anything about detention. A lot of people thought I had worked on Guantanamo or something, didn't really get the scope. Maybe it's obvious, but if I was thinking about a catalyst moment, it was 9/11. And then also, the Iraq War and fighting the Iraq War and being defeated by that process was really tough, which I know a lot of people are feeling now similarly.

A few weeks after the Iraq War started, I was just about to graduate and I went to the Critical Resistance South Conference, and I started to really learn about prison abolition and making those connections between why is the response always militarism, why is the response always carceral--what could something else look like? It really opened up my eyes to seeing the world a little bit differently.

AG: Central to Unbuild Walls is the connection of abolition and open border policies as two different kinds of movements. It’s something that Bill Ong Hing also spoke about when we talked to him. Do you still see tensions between these different movements? Do you see your work as bringing these groups together?

SS: I strive for the work that we do at Detention Watch Network to bring these movements together. I mean, the whole reason I wrote the book, the whole reason the book is called Unbuild Walls, yes, it's about those physical walls, the border wall, the detention center walls, the prison and jail walls, but it's also about unbuilding the walls between our movements, which has caused harm when we have those walls set up. I spend a lot of time dwelling on this in the book. The more mainstream immigrant rights movement, in the last couple of decades, has put forth this idea of immigrant innocence and the we are not criminals frame and in the process accepting the framework that public safety should be a justification for immigration. Immigration, it's about labor, it's about opportunity, it's about family, it's about refuge, obviously. This movement’s decided we're going to lean into “the good immigrant versus bad immigrant” frame and just support those people who are good and don't have interactions with the criminal legal system. Or if they do, they are uniquely deserving of something more than the general population that has interactions with the criminal legal system. So I think for me, a lot of it was: how do the frameworks that we talk about immigration end up reinforcing criminalization, anti-Black racism, the prison industrial complex, mass incarceration, discriminatory policing, all the things that we're fighting both in terms of the discourse?

RKR: Right.

I think the flip side of that is that often when our movements are siloed, we also have wins on one arena that could end up being a loss for somebody else or for some other community. So an example of this is in Louisiana after some criminal justice reforms in 2017, they ended up having some 5,000, 6,000 prison beds that were unoccupied and communities that were dependent on the carceral economy, the economy, the jobs that were created by these facilities were struggling. Trump swooped in and said, "Okay, we're going to make these facilities into ICE detention centers." And Louisiana had some of the highest rates of detention at that point.

So when we fight for something and get a win, it doesn't necessarily mean that that detention center or that prison actually shuts down, it just means that actually maybe there's another population that's going to fill those beds. And so what does it mean to actually have interconnected movements? So those fights are considering the next steps of the wins, it doesn't mean we shouldn't celebrate, in every single way. One example is the Etowah County Jail in Alabama, which was really one of the most horrifying facilities in the country. When we got the Biden administration to actually end the use of detention there and stopped detaining immigrants, that was an absolute huge win and important to celebrate. And it was after numerous hunger strikes and work strikes and protests and organizing and work with families. So much work that went into it and work with journalists and advocacy.

So when we fight for something and get a win, it doesn't necessarily mean that that detention center or that prison actually shuts down, it just means that actually maybe there's another population that's going to fill those beds.

So I want to celebrate that, but that facility is still open. Alabama has a horrible incarceration rate, it's terrifying what's happening there. So I think those things for me sort of exemplify why it's so essential that we actually understand these as intertwined movements and make sure we're not hurting another cause in the process of trying to push for the thing that we believe should happen.

Propina

We’ll continue our conversation with Silky Shah next week. In the meantime, if you are interested in learning more about the work she describes. Consider supporting Detention Watch Network.

We’ll see you next week.