“We should want to invest in immigrants rather than building a system that profits from violence.”

Rafael Martínez reflects on the invisible costs of undocumented survival right now.

Early on in The Cost of Being Undocumented, we write:

Our lives are divided into a series of befores and afters—moments that irrevocably alter the terrain of where we’ll go and who we’ll become.

And so, it is necessary to remind readers that this conversation with Dr. Rafael Martinez, assistant professor at Arizona State University, was conducted in one of those befores that we didn’t know was a before.

Dr. Martinez discussed his book, Illegalized: Undocumented Youth Movements in the United States, before military helicopters, tanks, the U.S. National Guard, and hundreds of marines were deployed to the streets of Los Angeles.

Make no mistake, though: this conversation took place long after xenophobic immigration policies divided families and caused chaos throughout this country. However, the actions we witnessed in this past week make most clear the kinds of violent costs incurred by the undocumented community of this country.

In this final part of our conversation, Dr. Martinez makes clear the kinds of invisible costs as they have shaped his family and his scholarship.

ANTERO GARCIA: With everything happening right now, do you still see the academy as a refuge?

RAFAEL MARTÍNEZ: The straightforward answer's yes. I still see education and higher education as a sanctuary space for undocumented immigrant students. With that said, I'm not speaking broadly or as an umbrella saying that higher education is this for all immigrant or even minority students. I'm saying it can be. In relation to my own experience, having positive mentorship and femtorship that were opening doors and opportunities have been essential and foundational for me. That’s one thing I've been very strategic about in my own work.

I always tell students that this is why we actively have to find those mentors, femtors, and support systems. The idea is making institutions work for everybody, which can require extra steps. It often means being transparent with students saying, “You can do it, but it's not easy and it will require extra work, unfortunately.” To me, that’s a responsible way of thinking that higher education could be a form of sanctuary for many of our immigrant students.

AG: One question we ask most folks relates to this publication’s name. La Cuenta refer to the invisible costs of the undocumented label. Thinking about the work that you've shared in your book or in your own life, if you could imagine a bill that accounted for what it cost you to live undocumented in this country, what would you put on it?

RM: I love that concept. I think it's such a powerful opportunity to share the other side of the equation, the other side of the truth, that we often don't hear in the general public.

Two things come to mind. The first one is thinking about how part of my book challenges the dreamer narrative: the idea that if you are incredibly successful and have incredible potential to offer the US government, that you should be prioritized for inclusion, while others don't receive that fair same treatment. I think my experience and the experience of undocumented youth who challenge this idea is precisely that the cost of one, that the cost of investment on immigrant populations produces the return on that investment every single time.

I don't think that I'm exceptional, but I think that I'm a product not necessarily state or government situations, but again, of people investing in me and opening those doors. Now, I'm able to return the investment in so many ways to students. I think that it shouldn't be an exceptional case. It should be an opportunity to say that if we do this for other immigrant communities, we would have that larger return of investment.

The argument in my book is that instead of putting our investment as a country on systems that detain and deport people, because those are capital economic systems of profit, we could actually gain even more by switching the function of those immigration system. And so, I think that the general public would hopefully see the human rights violations that happen as the cost of these systems. But they’d also understand, yes, we should want to invest in immigrants rather than building a system that profits from violence.

On a smaller scale, I’m thinking that, again, immigrants contribute at every level. I think about my parents' trajectory, which is obviously different than mine; they don't have a higher education. But I feel like their every step of the way they have been contributing. The US government has held them back by not giving them the same opportunities. They have to live in a very minimalist way just to be able to subsist. But because they have to live in this very minimalist way, their opportunities to contribute to the US can only be the minimum as well.

I think of my mom. She's a garment worker, that's why we came to LA. I think my mom would've had the talent to be an entrepreneur and create her own businesses and work with models and do all these really amazing things. But the US is not set up to support immigrant communities like that--to see that return in investment. So those are the two parallels that I'm thinking that's both personal, but also that in my book, I'm making and hoping people would see the cost of the immigration systems that we built in the United States.

“I think my mom would've had the talent to be an entrepreneur and create her own businesses and work with models and do all these really amazing things. But the US is not set up to support immigrant communities like that--to see that return in investment.”

AG: I love that. Your mom is a wonderful example: she makes these brilliant contributions, but that brilliance in some ways is dimmed by the expectations of the United States of what she's “capable” of doing. Those barriers were presupposed by the United States in many ways.

RM: Yep.

AG: Is there anything else I should have asked you?

RM: One thing that was really important for me in the book is centering knowledge production in terms of the organizers. I hope that comes across. But also I was very intentional in citing other UndocuScholars throughout the book. That was intentional, saying, “Of course, I'm going to cite all the folks that came before us and have done great work and that we should acknowledge.” But I’m also saying that there's a whole generation of UndocuScholars up and coming who are doing really amazing work and I think are going to revolutionize the field. I feel honored and blessed that my book is one of the few firsts, but I know that there's going to be more books coming, there's going to be more articles published. And so, my commentary to a general public and an academic audience is to keep supporting those folks. Citing is one easy way of acknowledging and reading their work. We have to keep doing that work with other UndocuScholars.

Propina

We are incredibly grateful for Rafael Martínez’s time with us. Please check out his recent book, Illegalized: Undocumented Youth Movements in the United States. If you missed the prior parts of this conversation, you can find them here:

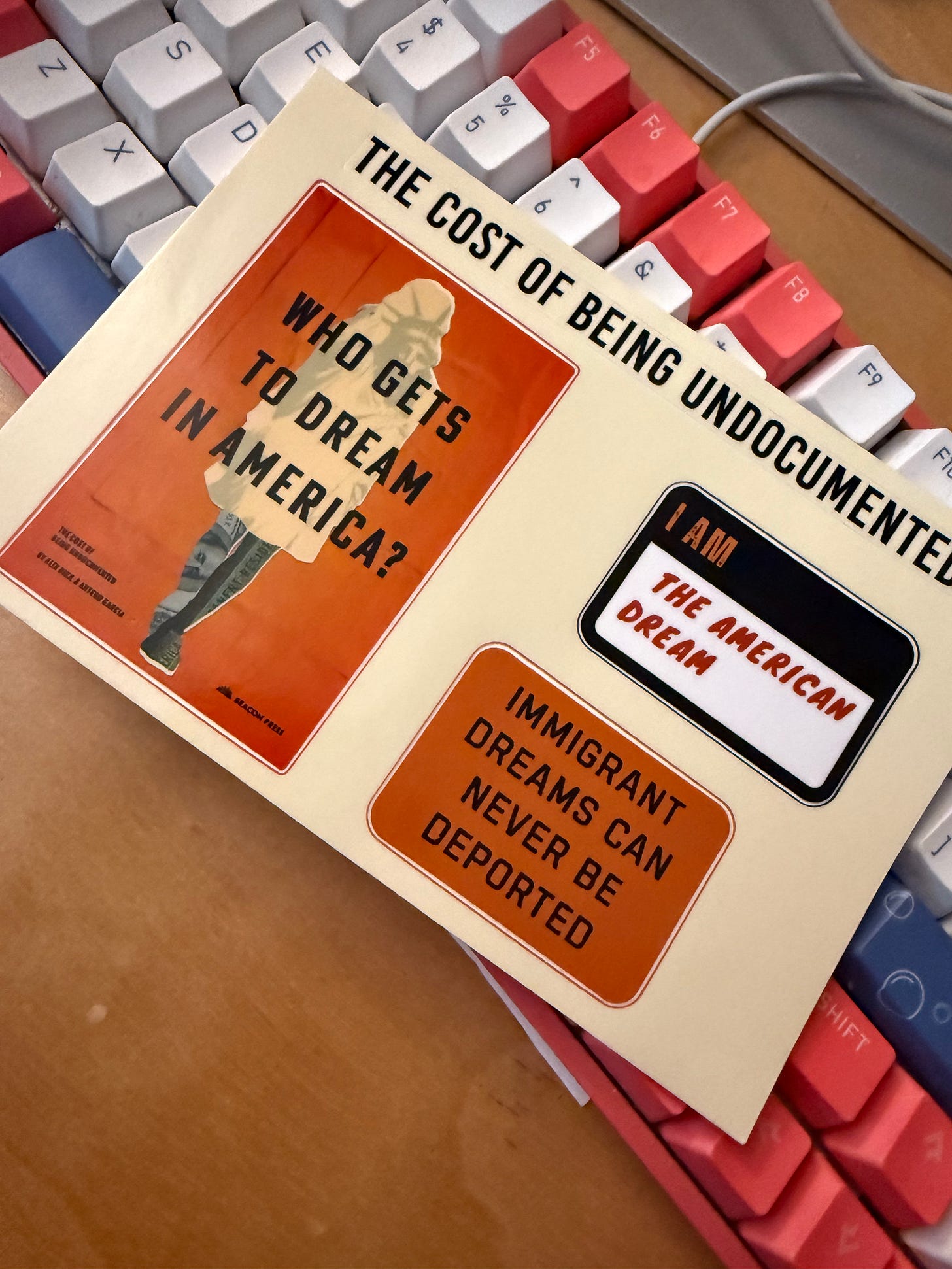

We are less than a week from the release of The Cost of Being Undocumented! If you have not preordered the book yet, please consider doing so and grabbing some amazing free stickers:

As you can imagine, this is an incredibly difficult moment to be sharing a book that feels so vital to the public narrative in this moment.

We are also bringing the book on tour and would love to connect with folks:

We’ll see you next week.