Uncovering the Hard Truth of My Immigration Status

"Although I spent nearly all my life in the United States, I am not the Chinese-American I always identified as."

This week, we are featuring the second half of Sirui Qin’s essay. Introducing their essay series, Sirui writes:

My story rejects the stereotypes that Chinese Americans are the model minority in the upper echelons of American society. It also dispels the belief that all undocumented immigrants are Latinos.

After I arrived in the United States, I thought that I was now Chinese-American. To be an American, I had to learn English. Going to preschool in the U.S. provided the perfect environment to hone my language skills. I picked up words based on context.

When I entered my classroom, my teacher said, “Everyone, please sit down.” My classmates then went to the chairs and sat down. That is how I learned the meaning of the phrase “sit down.” My teacher then introduced us to “centers,” which are corners in the classroom where we are to do different activities. I then learned that “centers” are places where people gather to do something. Over time, I pieced together these words to form phrases, then sentences. I was eager to practice the English I learned. Whenever I went outside, I would read every sign I came across out loud. Living in an English-speaking country allowed me to learn the language without memorizing lists from a dictionary.

My English skills were immediately put to good use. I became my mother’s translator, helping her answer phone calls and translate documents. At school, I helped translate for English language learners that spoke only Chinese.

Being a first-generation immigrant means figuring things out as they come along. No one in my family had received any education in the United States before. If I needed help on my homework, I would carefully peruse my textbooks to try to find the answer. Applying to colleges was especially challenging. In China, only one factor is considered in college admissions: a student’s score on the 普通高等学校招生全国统一考试 - pǔtōng gāoděng xuéxiào zhāoshēng quánguó tǒngyī kǎoshì (Nationwide Unified Examination for Admissions to General Universities and Colleges), which is shortened as 高考- gāokǎo (Baidu Baike). In the United States, many factors are considered, including personal statements, letters of recommendations, grades, test scores, resumes, and interviews. To understand this application process, I read many books and online articles on college admissions. I also had supportive educators that helped me in the process.

As an immigrant, I am incredibly grateful for all the education I received in the United States. Deep down, I thought that because I am not a “real American” and because I have vision problems, I have to work hard to prove that I am just as capable. This hard work is reflected in my grades. I spent a lot of time on my college applications, wanting to do my best.

One part of applying to colleges is filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). I grew up in a single-parent, low-income family, so I believed that I would receive the Pell Grant. I then came across the question: “Are you an eligible noncitizen?” I was unsure of my immigration status, so I asked my mom.

“Actually, you do not have any of the immigration statuses listed under ‘eligible noncitizens.’ This is because I am still working on your immigration case,” my mom said.

“So, does that mean I’m undocumented?” I asked.

“Technically, you have papers. You came to the U.S. on a visa. You have documents submitted to USCIS. So, you would not be deported. However, you are basically treated as undocumented when it comes to everything else.”

I sat there silently, in shock and disbelief. Although I spent nearly all my life in the United States, I am not the Chinese-American I always identified as. I am a Chinese citizen living in the U.S. I am not, by legal definition, an “American.” I had seen how the media portrayed immigrants- as “illegals” who are “invading” the United States. They are seen as a burden on American society. I had known about the numerous restrictions undocumented students face: they can not get a job or paid internships, which requires an Employment Authorization Document; they can not partake in federally funded programs, like the Fulbright Scholarship or certain research fellowships; they can not apply to the many scholarships that require U.S. citizenship or legal permanent residency; they cannot leave the U.S. for any reason; they cannot get a driver’s licenses and certain professional licenses; and a host of other restrictions (National Association of Secondary School Principals). I could not believe that I, too, would face those restrictions.

I reflected on my journey navigating my vision problems. At age six, my vision began to get worse. One day, we were assigned to color a picture of an apple. I used a pink crayon, because I genuinely thought that it was red. My teacher was disappointed when she saw my work. “Have you ever seen a pink apple?” she asked me.

“No,” I replied.

“Then you must color the apple red,” she said.

I was confused. I thought that I had colored the apple red. I took out my crayons and started reading the labels to see which one is red. I then used the actual red crayon to finish coloring the apple.

As the years went by, my vision became blurrier and blurrier. This caused me to take a long time to complete assignments. In elementary school, I was always the last one in my class to turn things in. I have to hold books a few inches in front of my eyes to see. This strained my eyes and made it difficult to concentrate on the words.

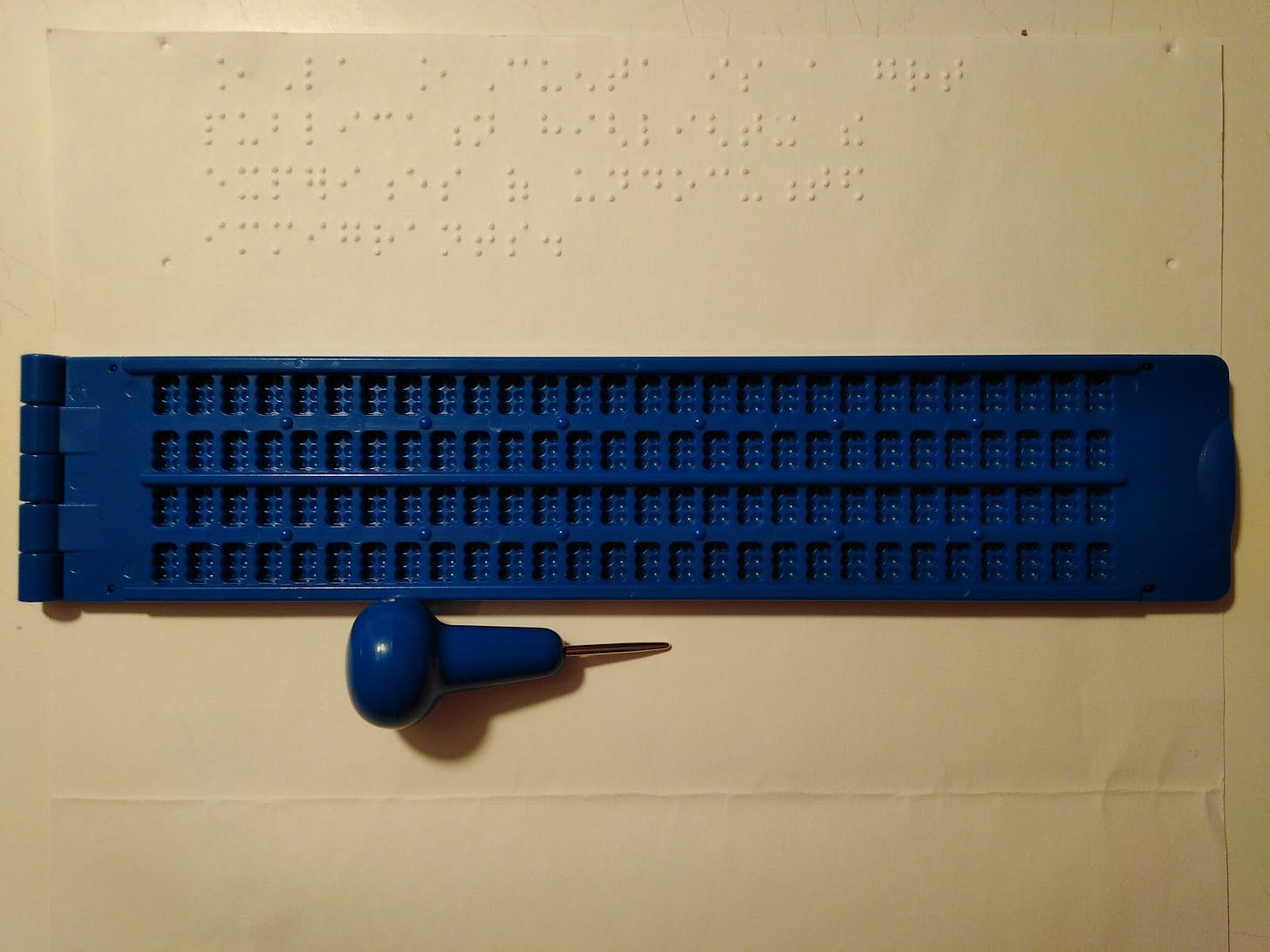

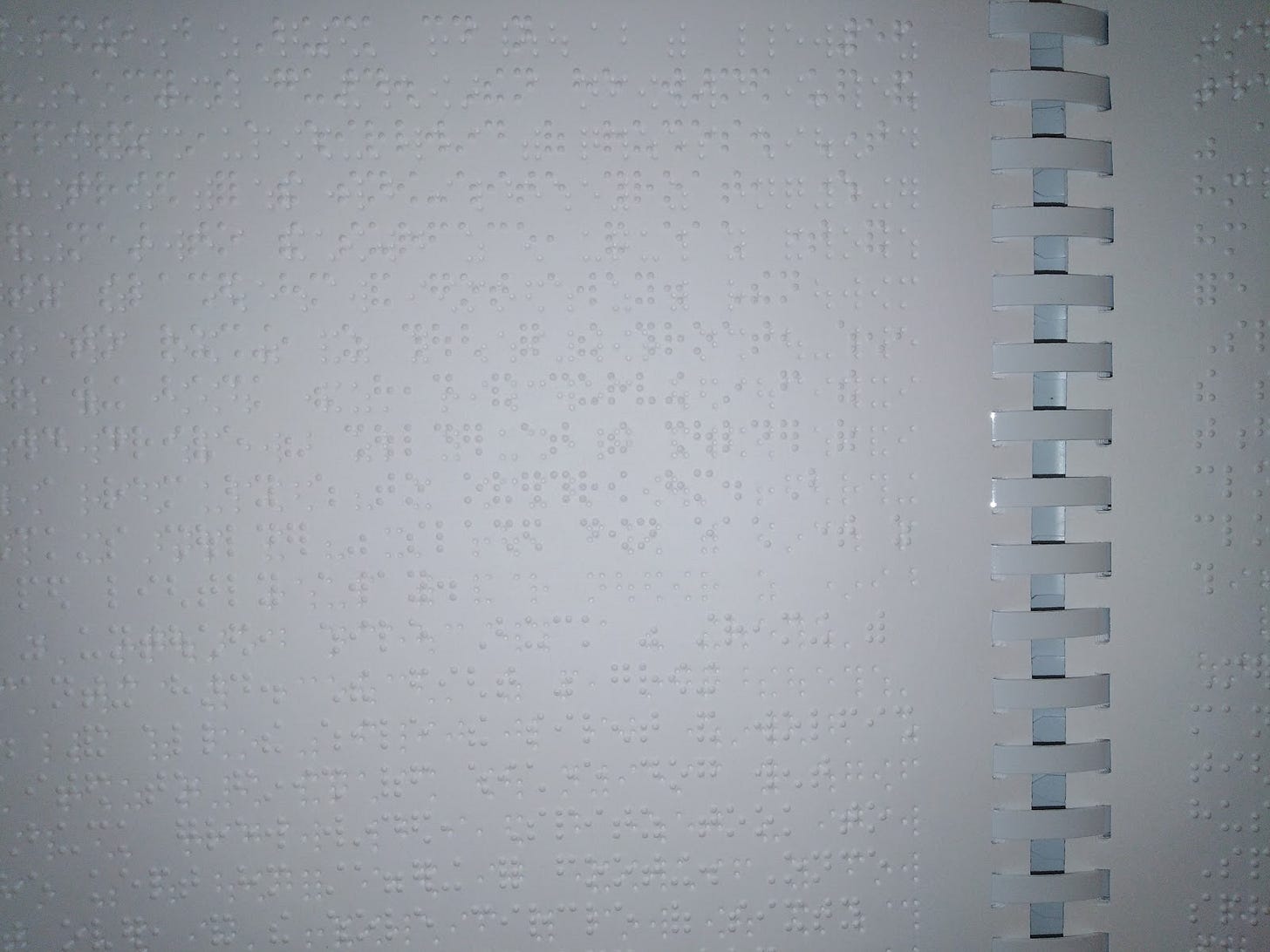

Later, I learned to do things in a more efficient way. I learned braille, how to use a screen reader, and how to use a refreshable braille display. With the protection of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, I was able to get the support I needed to succeed. I am now writing this article with the use of the Job Access with Speech (JAWS) screen reader and the Focus 14 Blue braille display.

The laws regarding people with disabilities acknowledge that they do things in a different way and support their needs. Although discrimination exists, I was able to obtain support and accessible technology so that my poor eyesight did not limit my education. Yet, my immigration status, which is purely a social construct, limited my opportunities.

Many young people are facing the same thing. They receive all their education in the United States, understand American culture more than that of their country of citizenship, only to find out they can not be legally employed after graduation. Some of them are undocumented, escaping dire situations in their country of origin. For example, being LGBT is criminalized in some countries (Human Rights Watch). Queer people have to flee their homeland and seek refuge elsewhere. As a nonbinary and asexual person, I feel lucky to be in the U.S. Some people could not afford an immigration lawyer, thus not getting the immigration benefits they are eligible for. Nonprofits that provide pro bono services usually have waiting lists that last for years. Some people are unaware of how to adjust their immigration status due to language, financial, or other barriers. Some people came to the U.S. on an H-4 dependent visa. Their parents hold high degrees and work in a specialized occupation in the U.S. on an H-1B visa. They grew up in the U.S. with H-4 status but aged out of the visa and became undocumented at age 21 (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services). Some have immigration cases that have been pending for decades. They all have one thing in common: Their immigration statuses are costing them their future opportunities and ability to fully contribute to American society.

My experiences as an immigrant prompted me to learn more about the legal systems that support and restrict us, paving my path to be a lawyer.

Propina

We want to thank Sirui Qin for sharing their essay with us. If you missed the first part of this essay, you can find it here:

How My Gender Brought Me to the U.S.

This week we return with a short essay series by Sirui Qin. In this first part Sirui reflects on their journey as a Chinese immigrant shaped by the one-child policy and how it led their family to migrate to the United States. It is imperative that we continue to dismantle false narratives of the immigrant diaspora. That we reject the boogeyman effect im…

We have been incredibly humbled by the stories and messages many of you have shared with us in recent weeks. If you have ever jotted an idea for a story, a picture, a poem, or any other message related to undocumented experiences in the US, we would love to share your contributions (and compensate you for your work). Please get in touch with any ideas you might have.

We’ll see you next week.

Works Cited

“#Outlawed: ‘The Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name.’” Human Rights Watch, features.hrw.org/features/features/lgbt_laws/.

“2024–25 FAFSA PDF.” Federal Student Aid, studentaid.gov/sites/default/files/2024-25-fafsa.pdf.

“H-1B Specialty Occupations, DOD Cooperative Research and Development Project Workers, and Fashion Models.” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 25 Mar. 2024, www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/h-1b-specialty-occupations.

“Undocumented Students.” National Association of Secondary School Principals, 13 Feb. 2018, www.nassp.org/top-issues-in-education/position-statements/undocumented-students/.

“普通高等学校招生全国统一考试 [Nationwide Unified Examination for Admissions to General Universities and Colleges].” 百度百科 [Baidu Baike], https://baike.baidu.com/item/普通高等学校招生全国统一考试/2567351.

Thank you very much for publishing my story!