On Navigating Daily Borderlands

Dr. Sophia Rodriguez reflects on identity and belonging in teaching and research with im/migrant youth.

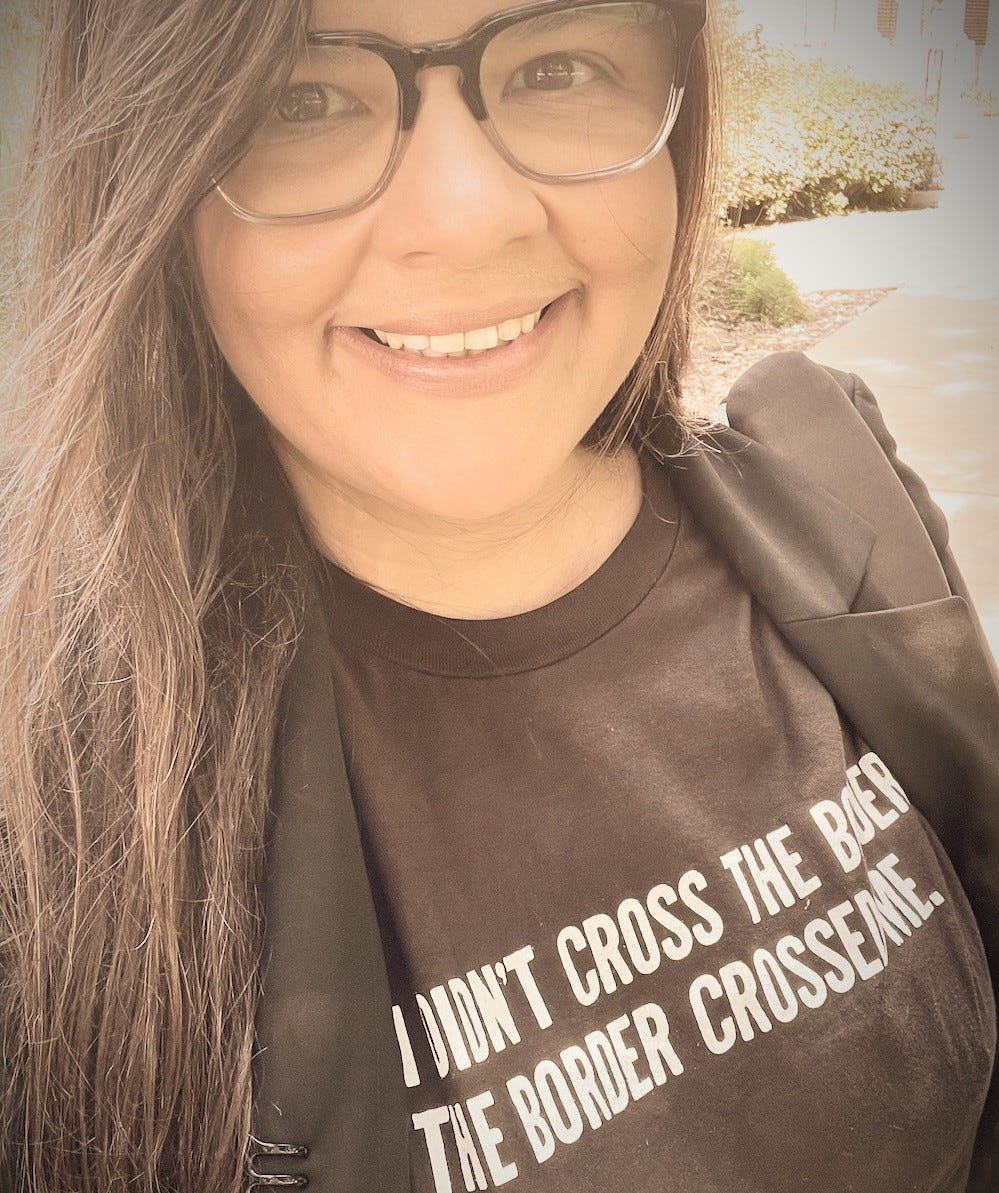

This week’ we feature an interview by Rita Kamani-Renedo, a doctoral candidate in Race, Inequality, and Language in Education at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education, with Dr. Sophia Rodriguez. Dr. Rodriguez is an Associate Professor in the Teaching, Learning, Policy, and Leadership department at the University of Maryland College of Education, and soon to be faculty member at New York University. Dr. Rodriguez’s interdisciplinary scholarship asks questions about the social and cultural contexts of education policy and practice, and examines the racialization of undocumented Latinx youth in schools.

I (Rita) am a former teacher at a high school for recently-arrived immigrant youth (“newcomers”) in New York. In my research, I think about how we can deepen and nuance our understanding of the experiences of newcomers. Even though there is no fixed definition of newcomers, they are often defined as foreign-born youth who arrived to the U.S. within the last several years. Within this simple definition, there’s endless heterogeneity and complexity. For example, some of the students I taught were born in the U.S. but raised by extended families in their countries of origin, while others had never been to the U.S. prior to their recent arrival. In my own work today, I think about the transnational racializations that youth experience as they cross multiple physical and metaphorical borders.

Dr. Rodriguez, through her scholarship, pushes us to think about the many intersecting layers of newcomers’ experiences. In this first segment of our conversation, Dr. Rodriguez shared how she came to the questions she asks about immigration and belonging, and how her positionality has shaped her experiences as a researcher.

I think that connection for me has always been personal.

RITA KAMANI-RENEDO: In a lot of your work, you've talked about your own positionality, your own identities, and how that shaped what brought you to this work. In your own words, what brought you to this work?

SOPHIA RODRIGUEZ: That's such a great question. It's so funny to have some years behind you. First, how I came to the work initially, so I actually started my career as a teacher in New York City public schools also. I worked in the South Bronx, and the majority of my students were newcomers, language learners from all over. The school I worked at…It was 100 percent non-white students. We were all alternatively certified teachers. So it was kind of a daily borderland, and I hadn't read [Gloria] Anzaldúa at that point, so I didn't even know I was living this experience of cultural difference in the school setting. There was just so much inequity and systemic racism, and I became really interested in the local community.

We had a couple partnerships with organizations, and we had a social worker, and we had some supports for the kids, but it was not nearly enough. I saw that as something of interest to me. When I went to graduate school for education policy—and I had never taken a sociology class—I was like, "Oh. This is where people talk about these things, in sociology of education at least…”

That was my teaching experience, that I had worked with immigrant students. There was so much in the school that focused on their language learning, and it was very English dominant, and not really honoring what they were bringing to the classroom. At the time, I had no idea that people had written about this. I didn't know Angela Valenzuela's work at the time.

When I started my grad program, I actually continued to teach high school because I wanted to stay connected to the classroom, and I worked in a school that wasn't a newcomer school, but I think one year I got 30 new kids, and they were from all over the world. Primarily, they were Burmese and Bhutanese refugees at the time, some Cuban refugees, and a couple others from Venezuela and Peru. They came and they had the shirts on their backs, and I ended up writing a grant, and was able to get money for different things to support their social-emotional wellbeing. I was really interested in what schools were doing and how they were partnering.

RKR: How were the questions you started to ask linked to your own history?

SR: My father was a Cuban refugee. He came to the US with the clothes on his back, and politically, he had a very different perspective…very English only, very much Americanized, "do well in school," and I obviously respect and see the value of all that, but it caused me to have sort of a… I don't know what to call it…like kind of a cultural identity crisis myself, which I had never thought of prior to getting my PhD, because everything gets ruined when you get your PhD!

[laughs]

In any case, I became really interested in how kids made sense of their identity and if they were split. I know you're interested in transnationalism too, like what does it mean to have these multiple parts of yourself?

What does it mean to have these multiple parts of yourself?

Kids were racialized—at the time, I wasn't thinking about that language—but they were being positioned in a certain way by the schools to leave parts of themselves and have that subtractive experience that Valenzuela talked about. I observed that in my teaching and my everyday lived experience, and that was something I became really interested in: How are kids making sense of their identity as immigrants? As—in my case, I was interested in the Latinx population—as Latinos, as diverse groups, while also being ascribed certain identities by the school and by society?

Kids were… being positioned in a certain way by the schools to leave parts of themselves.

That was kind of my initial interest in the relationship between identity and belonging, and part of it was that I was trying to figure out my own identity. As I worked more with Latino kids during my dissertation, I found myself talking about my identity in ways that I hadn't discovered before. I think that connection for me has always been personal.

RKR: Given that you have written a lot about how your identities have shaped the work, how has that changed? Are you thinking about that differently now than you did when you began as an earlier career scholar?

SR: 100 percent. I harp on my students all the time about their positionality, and then I don't always do a good job of writing about it myself…It’s interesting to me because, of course, I have privilege in the sense that I'm a professor. I've moved into a middle class or probably upper-middle class role. There's a great book called Limbo, about moving from growing up poor to being not poor anymore, and that challenge of moving through the working class, while still being connected through your family.

I think I've always been able to connect with the kids I've studied—even with the privileges of having citizenship—because I grew up poor, because I grew up in a really tough situation that really mirrored a lot of the kids’. We talked a lot about that…I've always talked a lot about family and poverty and kind of how I navigated that, and that's a big piece of my identity. My family is not rich just because I got a PhD.

Those things that I navigate now in the academy are really difficult, and I think it's a way for me to connect with the youth, even though I still do have the privilege of being a researcher and a PhD and a resource to them. I think how I've shifted is instead of thinking about my identity, it's now more about how I can connect with them. Julie Bettie talks about this.

I love her book, Women Without Class, she talks about the stories that we hold in common, and I think those are things as an ethnographer I've always been able to stick with, while acknowledging my difference and my privilege as a citizen, and now as a professor and researcher.

Propina

Next week, we will share the second part of Rita’s conversation with Dr. Sophia Rodriguez. Check out Sophia’s website to read more of her scholarship, see her project’s blog, and peruse the various resources she offers to educators and researchers.

We’ll see you next week.

I love Dr. Sophia Rodriguez's work! Thank you.