Matrescence is defined as the process of becoming a mother: those physical, psychological and emotional changes you go through after the birth of your child. It was first coined in 1979 by Dana Raphael and now used by anthropologists to describe this tender phase in the same way we might describe the process of adolescence. This term, rather new for me, would have been a helpful acquaintance several years ago when I first became a mother (or honestly like last year when ya girl was struggling with PPD). When putting together part two of our interview with Josie Del Castillo the term matrescence called to me. I listened to the recording of our conversation constantly and began to see how Josie approaches her art similarly to how she approaches motherhood: raw, honest, and courageously vulnerable. But I especially saw her openness about struggling with motherhood, how it has affected her identity, her life, and her artwork. I then also began to see how this process of becoming a mother affected me, not only with my first child but with every pregnancy. Every time I restarted this process, I came closer to my most authentic self; it was a gruesome process that we often don’t even know we are in. It’s a process where you feel like shit all of the time.

I wondered, if I had approached this process the same way I approach a writing project, the way Josie approaches her artwork, if I had felt differently about the process If maybe I might have felt more comforted by matrescence over postpartum depression would my becoming have been less painful? If only we were given the opportunity and the release to be in the process of becoming we wouldn’t have to constantly be in this push and pull between Self and Mother. Our normalization of a Mother’s Guilt might be null and void. Motherhood wouldn’t feel so heavy, and Mother wouldn’t be an all consuming new role made to replace the Self we were before we became mothers. Matrescence is still just a little baby and it has no money and no research because again, the patriarchy continues to hold us hostage.

Welcome to the conclusion of our conversation with Josie Del Castillo: Mother. Am I? As in, is this really who I am, is this all I am now? Answer: No.

If you missed the first part of this conversation, you can find it here.

CHRISTIÁN PEÑA: What do you think happens to women when they become mothers? Personally, my own artistic and creative endeavors took a backseat role after I had my son. My creative process changed, I felt so unsure of myself and whatever creative things I wanted to pursue felt almost selfish and there wasn’t much support from anyone for me to pursue anything if I really decided to.

JOSIE DEL CASTILLO: Because they were expecting you to lose yourself. And that is one thing that I have fought really hard against. I used to tell my partner all of the time when we were together — “I don’t want to lose myself, man.” Because I could see it in myself. I began to feel my sense of self start to slip away from me. So I had to fight really hard to get everyone including myself to understand that my work is separate from my being a mother.

I began to feel my sense of self start to slip away from me. So I had to fight really hard to get everyone including myself to understand that my work is separate from my being a mother.

CP: I think that’s incredibly powerful, considering how much the patriarchal systems thrive from our submission and our loss of self. And children deserve fully realized, fully human parents.

JDC: Exactly. And also because I love my daughter and I am a flawed human I reject the idea of the “perfect mother.” I could definitely be the kind of person that might fall toward the negative sides of motherhood if I stopped making art, if I let my self go and think and feel “Oh, having a baby ruined my life.” No le quireo tener rencor proque no hice lo que queria hacer.

CP: Honestly, I don’t think that could happen because of the art and the work that you do. You have never followed the expectations of what an artist should be, what a woman in a body that is not thin and white ought to be. I think it’s in your nature to reject those very things that would deprive you of your true and authentic self. It’s no surprise that you are doing the same thing in your practice and work as a mother.

What brought you to the work that you do now, the nude self portraits, and how long did it take you to feel grounded in that work?

JDC: Thank you. It took me a while because, when I first started, I didn't know what the fuck I was doing. But it came naturally, it was just an instinct that I followed. I painted my first nude in 2015 and I just couldn’t stop. And like I said it wasn’t easy, I used to get comments like, “She’s so full of herself.” or “When is she going to paint something else?”

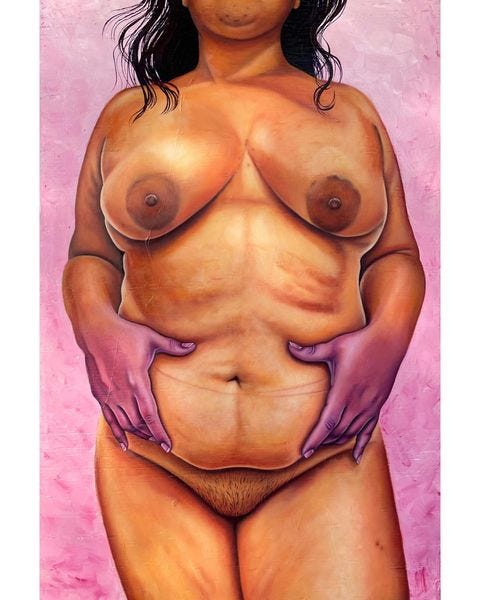

I think the plus size movement sort of began around that time or something about that movement and my rejection of it sparked this desire to paint my own nude body. Because all of the plus size models had these really nice curves with flat stomachs, nice boobs, pretty slim faces. I didn't feel like I even fit the plus size mold either, I still didn’t get to see a woman with my body type. I didn't get to grow up with that and the plus size movement also set us up to fail its standards so I felt like I still didn’t fit in. That was kind of a motivation—and it sounds really thought out—but at that time I wasn’t processing my work that logically. It was very much a sort of unconscious desire, or need pulling me toward that work. I just felt like I had to do it. Now that I think about it, all of those years of not giving a fuck and painting what I wanted lead me to where I might be now as a mom. And that’s why I painted that nude of me pregnant, the one where you can see my entire coochie.

All of those years of not giving a fuck and painting what I wanted lead me to where I might be now as a mom.

CP: That painting is amazing, one of my favorites.

JDC: Thank you. My mom was like “Josie, que va decir la gente?” — she was sort of taken back and she’s very supportive of my work and has never questioned it, but she saw it and how explicit it is and — I mean it's all my coochie you know? But I pulled out all of my research and my little art history and explained the artist that I am referencing and telling her, “I’m doing it because of this.” Just trying to educate her on the purpose of this work and why artists have taken this approach. Like I’m not just painting my coochie just for fun. There’s a reason.

CP: Is this something that you have encountered before? When you consider how machista and violent toward women’s bodies the Latinx culture can be, have you encountered machista sentiments about your work from others or within your own family?

JDC: You know what? I have never received negative comments from my family. And actually I don’t think I have ever asked them what they think about my work. I should probably ask them haha. They just support me. They just show up for me. They traveled to attend my MFA show, both my mom and my dad. And my mom came up to me and told me that a woman approached my dad and asked him, “What do you think of your daughter’s work?” like trying to get a reaction out of him — or honestly I don’t know why but they got weird energy from her like she was trying to instigate or get a reaction from my dad. My dad just told her, “Pues a ella le gusta ella lo hace.” And I asked them “Who the fuck was this lady?” They told me who it was and then of course the interaction made sense then.

All of that to say, I was surprised that my dad responded that way. You know he was always a little machista and at that time was pretty much still, machista which is like — he has five daughters, like come on. But I think he’s learning and he’s healing from his own traumas. I see him with my daughter and I think, “es muy buen abuelito.” When he’s at my shows he’ll be taking pictures of my paintings on display. So I think he’s proud. And I think they are proud because they always knew I wanted this and it makes them happy to see me do what I love. In a way I feel like this is my way of repaying them for their sacrifices. Like pursuing what I love is repaying their sacrifices of leaving their family behind. My dad left his family and his life behind en Matamoros when he crossed so I feel like this makes up even just a little bit for that struggle you know?

CP: As the daughter of immigrants do you feel like you have to carry that?

JDC: Yes, and no. No because They’re very supportive of my work and respect what I do for myself and as a mother so I don’t really think about it like that. And sometimes yes, because they have made comments about what I do like, “Why don’t you paint like Frida Kahlo, or stuff that will sell easily?” or “Well, why don’t you become an art teacher so you can make more money?” And like I said its not easy being an artist especially in Brownsville and I have struggled financially and they have seen me struggle so it comes from a place of concern and wanting to make sure that I am secure because that is why they made those sacrifices.

CP: I really appreciate you taking the time to speak with me today. It has been incredibly fulfilling to discuss being a creative, an artist, and a mother with you. Before we go I would like to ask, how do you envision the future of your art practice and what themes or ideas are you hoping to explore in your upcoming work?

JDC: Motherhood is definitely a theme that keeps coming up for me and that I hope to explore more. I want to be completely honest and raw about the good and the bad aspects of motherhood. Right now if you google motherhood art — es todo que “Es una bendicion” or “Lo mejor que me pazo en mi vida.” And yes of course but I want to explore more of the days where I am like “Fuck, I want to take a break from being a mom.” or when I feel like I don’t want to be a mom. I don’t want to be a mom but I love my daughter. More of that. I think that is an important conversation to continue to have — I don’t know how I am going to incorporate this into my work with my self-portraits but I definitely want to explore it. And like I said, when I first started painting my nude body I was like, “I don’t know why I’m doing this or how but I have to do it.” I think I’ll just have to take the same approach and see what happens.

Propina

We are, again, grateful for Josie Del Castillo’s time. If you are interested in seeing more of her work, keep an eye on her Instagram, where she’ll also post updates on upcoming shows or work she may be selling in the future.

We’ll see you next week.