When I was a project manager for a small asphalt company in South Phoenix part of my job was mapping out the streets on Google Earth. I would trace my cursor alongside the edges of the street and the sidewalk so I could get as accurate as possible in order to estimate how much material the crew would need and how much the salesmen would need to charge the client. I hated that job. It was just me and this white woman who spent her leisure time talking shit about anyone and everyone on the crew and in the main office in Utah in this small shitty office on 16th street and Broadway.

On the days where I pretend to work I took to Google Earth and traveled the world. One day I had asked my mother or my uncle – I can't remember—for the address of the home mi Abuelito Pedro built in Jalisco. I entered the address into the Google Earth search bar and, in Street View, I walked the dirt paths and concrete sidewalks I imagined my mother walked as a young girl. I would stop in front of every place I had heard her talk about or reminisce with her sisters. I did that every time I was avoiding my work or my dramatic coworker.

I entered the address into the Google Earth search bar and, in Street View, I walked the dirt paths and concrete sidewalks I imagined my mother walked as a young girl.

My virtual walk through La Villa Purificación always ended in front of the tall, terracotta-red house mi Abuelito Pedro built. I focused on each section of the house where some of my mother’s siblings expanded with rooms and space to fit their own families. I wondered what it looked like on the inside, and what it felt like to be there. I once joked that it looked like a very tall Rancho Market. I ached to be there instead of my office in South Phoenix where my only window had the view of a gray wall with barbed wire coiled on top of it. Working in a place where my colleagues and superiors dropped their enthusiastic Trump conversations when they saw me coming.

One evening, I found my father pacing the kitchen absentmindedly and in a low whisper told me that my mother needed me. “Tu abuelito se murió.”

When your grandparents are as old as mine, seventy five years to be exact, with ailments like mi Abuelito’s – the diabetes that took pan dulce y arroz con leche from him--you worry about the day they may leave you. I never really knew Pedro Llamas. But I knew that my mother adored him – adores him, always and forever. When my mother was a young girl, Pedro decided to come to the states to find work. His time here was cut short when Doña Lupe told him that his daughter, my mother, had refused to eat anything since he left. You see my mother would not eat unless she was sitting on her father’s lap. And when he left, this ritual at meal times was taken away from her and with it her appetite. After a week, he came back. “Que por que la niña no queria comer.” And he never left again.

Pedro Llamas was loving, and he was funny. Every time my mother was on facetime with him she would give me the phone "para saludar”. I would ask him “Como esta abuelito?” and he would say “ahy mija, pues ya casi me muero.” and he would throw his head back in this great big laughter and my mother would laugh from wherever she was like it was the first time she had heard that joke. He was constantly joking about his death. Like it made him or maybe even his daughter feel less afraid of the day that he might leave her. He was tall, and always wore a sombrero and knew everyone en La Villa and could tell you all the juicy gossip he had recently heard about tal y tal persona.

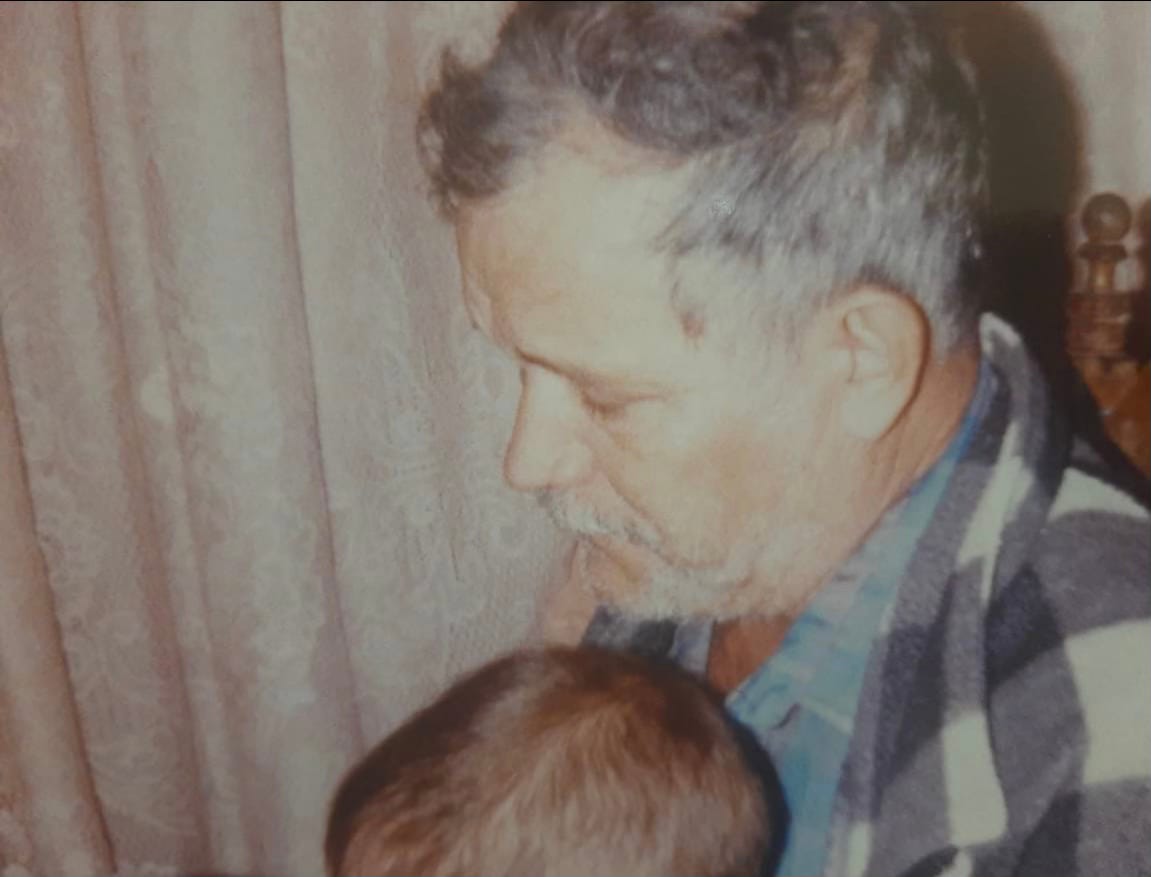

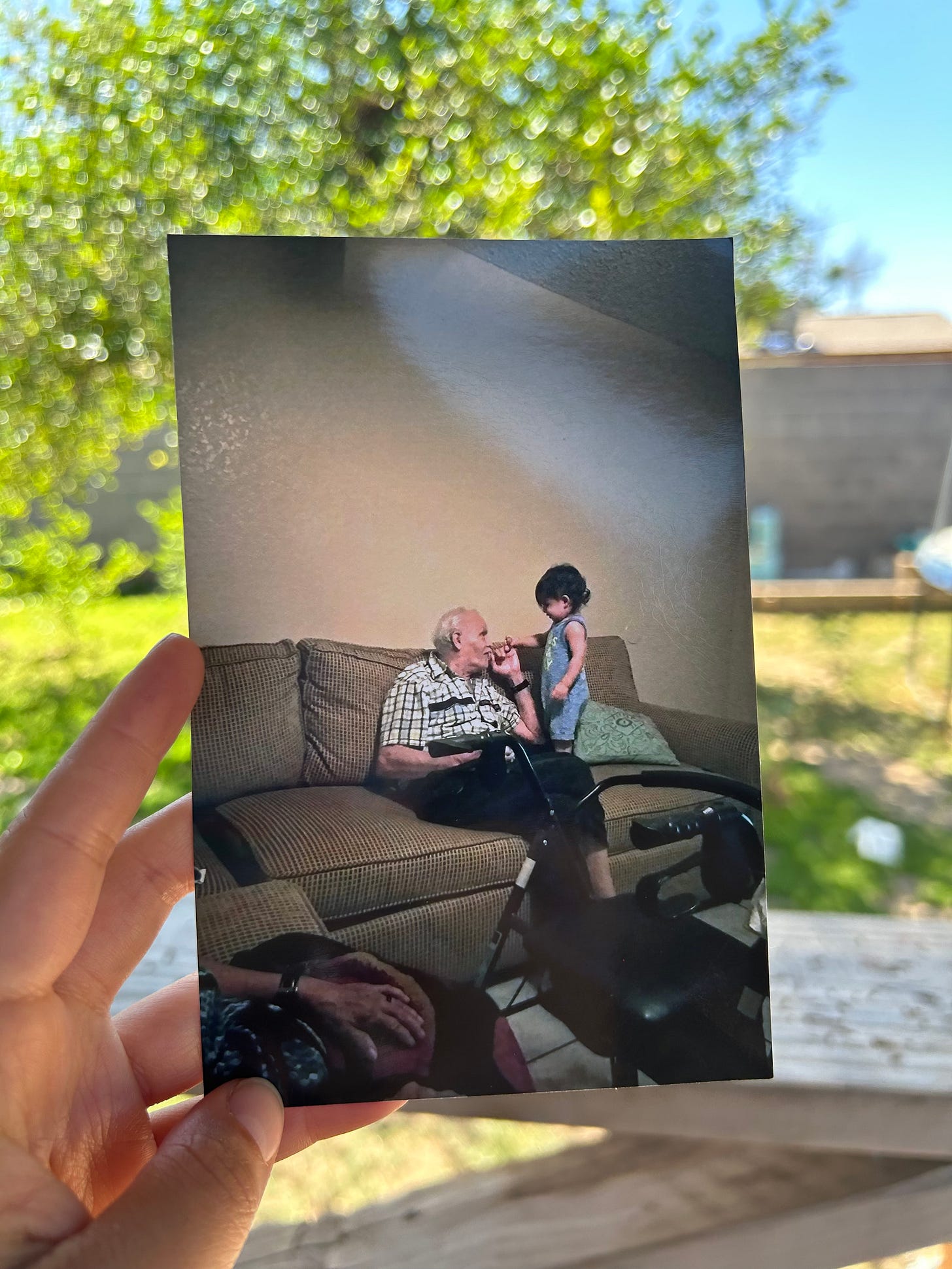

When they came to the States for the first time I was pregnant with my eldest daughter and my son was a year old. While he was here I was tasked with testing mi abuelito’s blood sugar because my mother couldn’t bear to poke the tips of his fingers and watch him wince in pain. So every morning my mother would set everything up and I would prick his fingers. I would take his hand in mine and prick his finger, sometimes two or three times because no blood would come out. “Ya se me acabó la sangre mija, se me seco de tanto picotazos.” Then we’d take a break to settle our laughter and try again on a different finger. At night, he would play dominos with my mom and dad and mi Abuelita Lupe who always had a cup of black coffee before bed. He would play with my son and if he ever caught him rummaging through cabinets or making a mess he would say “Ese niño es bien trabajador.”

I have only ever seen my mother cry twice. First when I was six and she had a fight with my dad and we hid from him in the darkness of their bedroom. Her body pressed against the door to prevent him from opening it. How she wept, how her voice cracked and changed when through her tears she said she missed her family. I remember so vividly in that blue darkness how urgently she asked me not to tell my father that she cried. And then, when mi Abuelito Pedro died. She cried so much then that everyone – but especially my father avoided her. The evening he passed I found my mother sobbing in her bed, curled up with a pillow and her phone in her hand, her face partially covered by it. This strong woman – when I think of strong I think of the way she describes her own mother “Mi mama era fuerte, bien dura.” seeing her that way, incredibly human and to approach her and to hold her was the most intimate we had ever been in my life. But somewhere deep down as the eldest daughter I had always been preparing myself for this moment. For the moment my mother would lose the love of her life, her dad, and I would have to be there to comfort her. I had done a ritual, one I learned from some teachers at a school for hermetic sciences or ritual magick, when Devin’s Nana Honey passed. I recited that ritual every day in front of a candle we kept lit until it went out on its own. I quickly scribbled it onto a piece of paper and lit one of my mother’s candles and set it on her dresser. My way of comforting her was ensuring that mi Abuelito Pedro’s soul had a light to support him on his next journey. Even if she might think of my own spiritual practice as cosas del diablo. Prayer, I have learned, is prayer no matter the religion. She did not protest my ritual.

That first week after mi abuelito’s death, I was texting family I hadn't spoken to in years. My cousins and I would check in with each other and talk about our mothers’ mental health. One tia refused to talk to anyone and looked to blame her brother for his lack of care, for his inability to ensure their father’s health and safety, she looked to blame and rage her pain away. I understood that. One tia found solace in Facebook posts and family group chats. My mother sat in her room, in the darkness and avoided people so no one could see her cry. I felt nothing. Sadness yes, for my mother. But I felt nothing for myself and it felt almost disrespectful to grieve for someone who I hardly knew and no one could grieve or hurt the way my mother did for her father’s death. But he was my grandfather. I wanted to know him the way my mother did, I wanted to know what it felt like to love him the way my mother did, the way her eyes glistened and she glowed when she spoke about her dad. I wanted for him to love me even a fraction of how he loved his daughter. Like maybe it could heal my father wound. I wanted to know what it felt like to have grandparents who were not separated from you by a border.

Mi Tio Salomon sent my mother a link where she could watch a live stream of mi Abueltio Pedro’s funeral about a week later. When she joined, there was nothing but a black screen and some sound. She was furious and hurt and wouldn’t speak to her family in Jalisco for months after. No one tried to remedy the technical difficulties and she felt offended and left out. Because of the borders that separated her from him for twenty plus years, this was the only way that she could attend her father’s funeral.

Because of the borders that separated her from him for twenty plus years, this was the only way that she could attend her father’s funeral.

After mi Abuelito died, the urge to visit his home via Google Earth returned with a force. I stood in front of that tall Rancho Market-like house in street view, wondering what material he used to build it and why he chose the colors he did. I tried to imagine what it smelled like there, and all my senses could offer was wet clay or the way the parched concrete desert of Phoenix smells after a sky full of rain blesses us for a day. As I sit here and write this, a knot forms in my throat and it is the first time I cry over his death. I cry over the borders that denied me the warmth of his arms, the connection to that pueblo, to its customs and its gentle beauty. I would give anything to hear my mother’s laughter as she’s speaking to him on the phone. Anything to hear one last phone call end when my mother and my grandfather part and she says to him “Lo queiro mijo, se me cuida.”

Living between worlds and borders is halted breath, it is always waiting to belong where you may never be able to return to. And I am no stranger to a body always waiting for breath and my grandfather’s arms.

Propina

Using Google Earth, what streets can you digitally walk today? How have they changed or how has your access changed to them over time?

If you’d like to curate a tour of your life across borders and share your journey - drop us a line!

We’ll see you next week.

I am not crying 😭 😭😭😭😭

Beautiful read!