"I felt like I had taken this poison that I had inside, and I turned it into something beautiful."

Erika Sánchez on healing through publishing and the costs of immigrant survival.

At readings and events, it’s not uncommon for people to tell Erika Sánchez that her books changed their lives. Perhaps somewhat surprising is that one of the people who was healed through these books is Erika herself: “Writing [Crying in the Bathroom] was one layer of healing,” she explained. “And then publishing was another.”

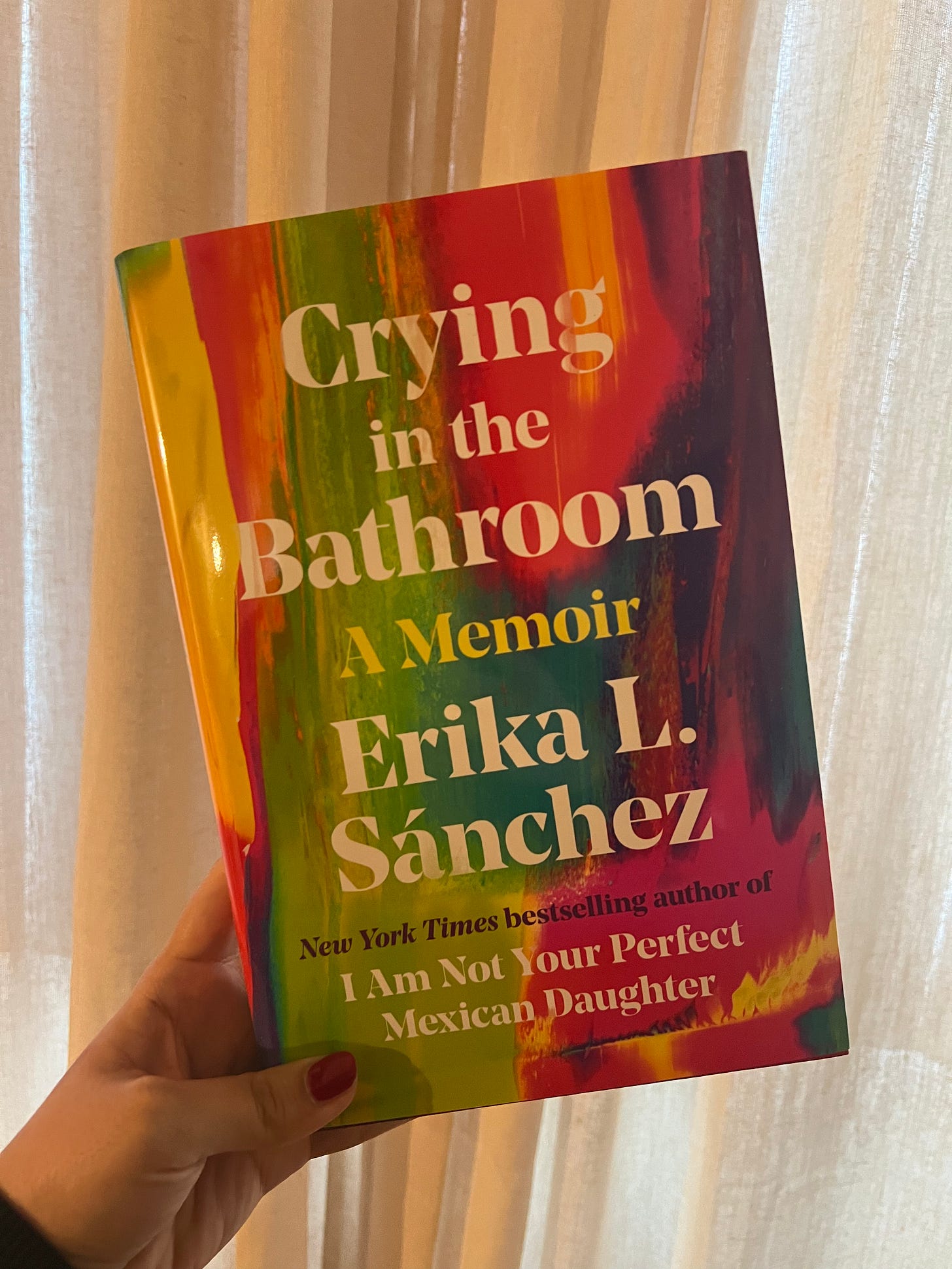

Last week, we discussed the costs of book banning and Erika’s personal experiences with her work being challenged across the country. This week, our conversation focuses on how her recent memoir, Crying in the Bathroom, has been a vehicle for healing as well as how her family’s history around immigration is shaping her latest work. Finally, Erika reflects on the anger she carries with her after DePaul University chose not to renew her contract last year.

If you missed the first part of our conversation, check it out here:

ALIX DICK: I want to start on a personal note: we just finished the draft of our book, and honestly, the process has been so difficult. I’m a private person; writing about my personal experiences has been incredibly hard. I’m wondering if Crying in the Bathroom was also a painful book for you to write.

ERIKA SÁNCHEZ: Oh, my God, yes. Excruciating. There were parts where I was just sobbing. It was something that was extremely taxing, but it was also really cathartic to turn all of that into a work of art. To know that it wasn't all in vain, that these things happened. I feel like I healed a lot as a result of publishing [Crying in the Bathroom].

Writing it was one layer of healing, and then publishing was another. I get so many responses from people who are really grateful that I wrote about a certain topic. Mostly it's about mental health or not belonging to either culture. I've received messages that said, "Your book saved my life." I didn't expect that. And sometimes I have readings and people get very emotional and there are tears. That's a lot. But I'm so grateful that the book has been able to touch people that it's helped them heal in some form.

There was this man asking about the procedure I had done when I was suicidal, and then he got it done because I gave him some background information, and he's doing well now. Wow. The book introduced him to this treatment and he then got the treatment. You can't really measure the effects. Some people hate the book, whatever, I don't care. It's kind of irrelevant.

ANTERO GARCIA: That’s their problem!

ES: Yeah, it's their problem. Once it was out and people knew my darkest moments, I thought it was going to be really terrifying, but it really wasn't. I felt free. I felt like I had taken this poison that I had inside, and I turned it into something beautiful. And it's now something that people feel healed by. And so that's really what matters to me. I don't care that people know about the worst moments of my life anymore, or that I made all these bad choices. It doesn't matter because I know who I am. I guess I'm just very confident in myself and who I am. And also, I don't need everyone to like me. That's something that I've had to learn as a woman.

AG: I regularly talk with students—future teachers, researchers, and professors that I work with—who share how much your books have profoundly impacted their lives.

ES: That's great ... even though, I don't have a great experience with academia.

AG: Oh yeah. We weren’t going to bring it up.

ES: Yeah. If you want to talk about that, go on.

AG: Well, part of why we’ve created La Cuenta comes out of recognizing the kinds of harm caused by research. Across the history of academia, research has inflicted immense harm on Black and Brown people in this country.

ES: Yeah, universities are deeply fucked up.

[laughs[

For real! I went in there guns blazing, ready to just tear stuff up. And I feel like I did, and my students reacted so well to that. I treated them like they were my equals, and we had great conversations. They felt comfortable. They were vulnerable because they felt safe. The work I did there, I'm extremely proud of. And sometimes I still feel a pain when I see the university or I get a note from an old student. It's something that will forever be a part of me. And I also feel anger because I was kept from continuing to do that--from teaching these radical concepts and critical thinking and empathy and self-care and all the things that I find important. That's how I taught, and I was very passionate about it. And to have that suddenly taken away was very jarring and confusing. I remember telling my husband, "I think I'm going to get canned." And he's like, "No, they would never get rid of you. You're amazing." He couldn't even conceptualize it. And when they did, and the response that I got, the outcry from students, was so intense and immense. I didn't expect it. And so, I am grateful for the experience, and I'm also incredibly angry about what the university prioritizes. They say one thing, but they do another. They want diversity, but they don't actually want it because why would they get rid of me when I was killing it?

Sometimes I still feel a pain when I see the university or I get a note from an old student. It's something that will forever be a part of me.

AG: Something I've learned from our conversation and your books is that you center empathy and passion in your work. It is a heart-forward approach. And the academy fundamentally doesn’t want to center Brown people--Brown women's—hearts. Your voice and presence threaten genteel society and how people are supposed to behave.

ES: Yeah. It's been the case my entire life. I look back on my life as a child … My friend and I refused to stand up for the Pledge of Allegiance. We just didn't want to. We were nine years old. We're like, “Not going to do it!" It's just like that sort of attitude that I've carried on, especially learning more and more and more about this country and all the terrible things that it's done and why I'm here, why my parents came here. It's a lot and I feel so exasperated, because it doesn't have to be like this.

It's been the case my entire life. I look back on my life as a child … My friend and I refused to stand up for the Pledge of Allegiance. We just didn't want to. We were nine years old.

AD: Returning to the name La Cuenta, if you could create a bill of the costs of what the United States has taken from immigrant families, from your family in particular, are there particular things you'd put on this bill for your parents?

ES: I think living with this terror of being found out. I can't even imagine what that's like to always be on alert everywhere. Something might happen, the police might come, ICE might come. There were raids in my mom's factory, I know that.

I’d also include cheap labor. I grew up pretty poor and it was because my parents first were undocumented, then they had documentation, which was amazing because of Reagan amnesty. But that didn't suddenly change their economic status. They were still very blue collar people. And so, we suffered just not having enough.

And I’d also include anxiety. Always anxiety. When you're poor, everything's an inconvenience, and everything's so complicated. I think about it now that I'm not, and I'm like, "Wow, I could just pay that ticket," but before, that could have broken me. That could have broken my family.

And these tickets here in Chicago are really... I don't know, they're aggressive. They issue tickets if you go five, six miles over the speed limit, and most people do because it's normal. You get a ticket in the mail and then what? I think about that a lot because I get these tickets and I'm like, "Fuck," but at least I can pay them. There are people who don't have that available to them, and it creates this domino effect of inconvenience, and sometimes it could lead to really harmful situations, getting evicted, losing your car. Life is so precarious when you're an immigrant, especially undocumented, and you're just at the whim of the world. You have very little say, very little power because if you make noise, people will notice you. So, that's sort of shrinking, and I see that with my parents where they're just very careful, quiet people, and then they have a daughter who's just bananas.

[laughs]

Life is so precarious when you're an immigrant, especially undocumented, and you're just at the whim of the world.

They're just like, "What the fuck is going on?" But now they understand for the most part that the work that I do is in service of them and other immigrant communities--women who have had very little choices as a result of their status, and women who have to stay in bad relationships and who can't move to an apartment because that's just not an option, the list is never ending.

AD: Yes, this idea that one little thing--one speeding ticket can literally just upend your life …

ES: Right. These are things that I'm thinking a lot about as I write this book. This woman is a mother, the protagonist, and she's undocumented, and all the hurdles that she has to jump in order to just survive, it's not even thrive. It's survive.

AD: To barely survive, right?

ES: Right, and then people still demonize you like you're a bad person because you came here without documents. That is so inhumane to think of it in that way, but that's the kind of shit that we're being told by all these politicians and all these fascists, including Trump.

AG: We are so grateful for you taking the time to zoom in on your work and this broader community struggle.

ES: There's so much talent in our communities and love and resilience. It's not just strife, even if that's often what we see.

Propina

Please check out Erika’s books if you haven’t had the chance.

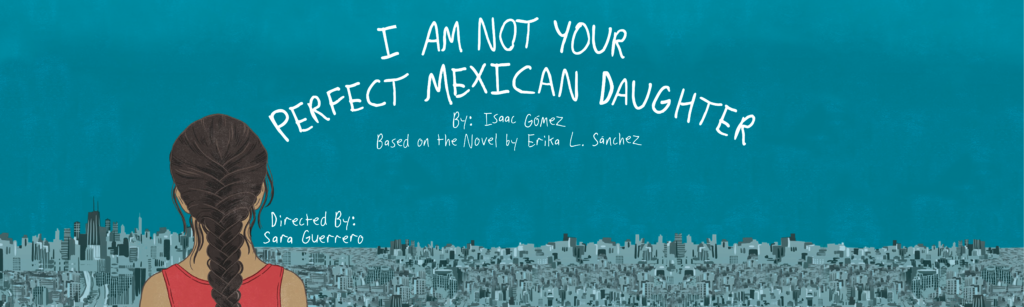

If you live in Los Angeles, a theatrical adaptation of I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter is running throughout the month of February at the Greenway Court Theatre.

We’ll see you next week!