“I believe in the work of being vulnerable. I call it scar-sharing. … People are way more open to reflecting on themselves if you're willing to go there first.”

Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez on the journey of vulnerable writing and connecting with readers

Reflecting on how her latest book, Tías and Primas, might have guidance for building a newer, freer world, writer Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez suggested, “I want people to view our family members very differently and have a lot more space for it.”

We can read Prisca’s book as a cartologically speculative gift. It maps the abundant spaces where new relationships and family configurations can thrive in the future. This week we continue our conversation with author Prisca, as she discusses the ways her book creates constellations of readers and growth, her process of collaborating with illustrator Josie del Castillo, and the often painful process of vulnerable writing.

ANTERO GARCIA: I appreciated the shout out to the work of Simone de Beauvoir in the first few chapters of the book. She was such a leading, radical feminist that I think sometimes slips below the radar for a lot of folks today. I liked how you incorporate her work.

PRISCA DORCAS MOJICA RODRÍGUEZ: It's a take on it for sure. She does all these archetypes, and I was thinking about how to make them accessible. It’s great stuff. My Simone de Beauvoir [book]’s got 100 tabs, but who's going to read this super fine print? Almost 1,000 pages. It's too much. So it was like, how do I write this?

AG: Another exciting name we saw in the book was Josie del Castillo, who created all of the images of the tías and primas. Christián Peña had an amazing conversation with her about painting and parenting in an earlier installment of La Cuenta. How did you end up working with Josie?

Lose Yourself

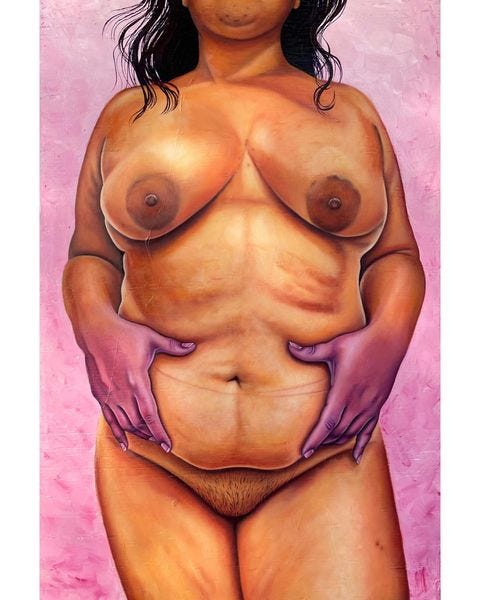

Josie Del Castillo’s art is a nice fuck you to a patriarchal society that is historically known for its violence on women's bodies. She offers us, as witnesses, the opportunity to step outside of the bounds of the dreamy, sunshine-and-rainbows fantasy of pregnancy, motherhood, and the female body through her i…

PDMR: I'm a huge, huge fan. I think her work for Latinas can be really impactful to look at. To see her naked body … to just to see a normal body--redefining a normal body--it is beautiful. I remember the first time I saw one of her paintings, which I ultimately ended up buying the original of. I was stunned. I cried. I’d never seen something like this. And so I went through the process of buying it, just so that I would be on her radar. I bought it, and then I had to pay her through installments, because artwork is expensive. And we ended up talking. I knew I wanted her to do my illustrations, but I wasn't going to be aggressive about it. After a few months, I messaged her and was like, "Hey, would you be interested? Set your rate." She had never done something like that before for a book like this. So she was really hesitant, but I really insisted. And she had read Brown Girls and liked it.

So we got together with my agents, we wrote a contract, she set a rate. And I was like, “Oh, you're pricing yourself too low!” So she reset her rate, and then we started it, and I when I was writing a chapter I would send her a synopsis. It's very scary to send people your drafts.

ALIX DICK: You're telling me!

PDMR: Around month nine into writing the book, I was almost done with the whole book, and I hadn't gotten any illustrations. I was starting to freak out because the publisher was threatening to give me the Rolodex. They were like, “We'll just put you with one of our graphic designers.” I knew they’d be mostly white, so I said no. I had a heart to heart with Josie. We were checking in pretty regularly, but she had given birth, and a single mom. I asked her, "So what do you need me to do to make it happen?" And she's like, "Well, can you come to Brownsville and take care of my baby?" She was laughing, but I said OK. 10 days before my birthday, I flew to Brownsville. I took care of her baby. I cleaned the house, made food, washed dishes, while she was in her studio making all the illustrations until she was done.

AD: Wow.

PDMR: It was awesome. And I'm a fan of hers, so I got to hang out at her studio, hang out with her. I was starstruck. It also gave me perspective. I had written, “The Childless Tia” and then I hung out with this baby, and she was nine months old at the time. And I remember it would be like 5:00 or 6:00 P.M., and Josie would be done for the day. I'd just be like, "I'm so tired. Here's your baby." I was so drained, and I had so much more sympathy for how exhausting it must have been for her to... I understood why she couldn't finish, way more than I understood before. Intellectually, I understood she was a busy single mom, but living in her house, and taking care of her nine month old, that was different.

It was fun. And it was a reminder that if you want this, publishing is really elite and exclusive, and if you're creating spaces for different people within that, then you have to put the effort into it too.

“If you want this, publishing is really elite and exclusive, and if you're creating spaces for different people within that, then you have to put the effort into it too.”

AD: You have been very vulnerable and generous sharing your tender heart with us. I was wondering if these books been really difficult for you to share with the world?

PDMR: Yeah. Awful. I don't like rereading my own stuff. I think if you listen to the audiobook for Brown Girls, I cry through a lot of it, and I still cry through a lot of it because I was saying things out loud that I never had said before. I was writing things down that I just kept inside me, and I thought it didn't bother me. I developed a few autoimmune disorders since Brown Girls that I haven't been able to figure out. With my therapist, we've just been like, "Your body's been fighting because you're safer not saying these things. It's better to not be vulnerable for your own wellbeing, so your body just wants you to shut up." And that's a thing that I'm contending with still.

“I think if you listen to the audiobook for Brown Girls, I cry through a lot of it, and I still cry through a lot of it because I was saying things out loud that I never had said before.”

Writing Tías and Primas, making it prescriptive, my body accepted the process a little better. It still was hard, and it still feels like I walk around with a dark cloud the whole time I'm writing. So it is hard to be in community with people. It's hard to talk, and it's just hard to be a person when I'm writing. And I know that that's just part of the writing process that I've signed up to do. Because ultimately, I do believe in the work of being vulnerable, and I do believe that if you... I call it scar-sharing. Little kids, when they're like, "Oh, I got this scar when I fall off my bike," another little kid is going to be like, "I got this scar when I fall off my skateboard," or whatever. People are way more open to reflecting on themselves if you're willing to go there first. I know that that's important, and that's a strategy that I'm utilizing, but it still sucks all the time.

AG: Does it feel easier when those words get to other people? When I read your books I know one version of you through that process. Is that scary? Liberating?

PDMR: I think it's scary and liberating. And I know that it's doing what I want it to be doing because I meet a lot of readers all the time and they're really quick to be like, "Oh, this happened to me." I've gotten the gamut of personal stories that I did not ask for, but, in some ways, by writing what I did, I did ask for it. And so they feel like they can finally say things that they haven't been allowed to say. I think it's worthwhile. It doesn't make it easier, but at least that is not something I'm making up in my head that is going to happen.

“I've gotten the gamut of personal stories that I did not ask for, but, in some ways, by writing what I did, I did ask for it. And so they feel like they can finally say things that they haven't been allowed to say.”

AD: I can totally relate with what you are saying. Sometimes I want to vomit when I read parts of my book because it’s not only a book, but also real life. When I put it on paper, I will read it and say “What? I went through that? What the hell?" Did you ever have one of those moments where you have the shock of realizing that you survived certain things?

PDMR: Yeah, definitely. There's an element of like, "This feels good. I can move toward the next step of my healing." But I can't reread a lot of stuff without still getting choked up and realizing, "Oh, that's still something I'm carrying around, I'm still processing, I'm still moving through." But, yeah, I think it's the beginning of it for me, for sure.

AG: In the introduction to Tías and Primas you write, "What I'm trying to do is imagine a world where we all get to exist, and I'm speculating on what their existence does to confront our internalized biases as objects of the patriarchy, white supremacy, and capitalism. I'm imagining worlds for us. I'm imagining worlds where we are more than objects, we're subjects, and we can exist fully." Alongside naming the women in this book, do you have expectations for readers as to how they help make a new world possible? What do you want readers to do in building that world with you?

PDMR: There are a lot of ways in which we can throw away people in our families without the understanding that systemic oppression has impacted them too, in the way that we'll be like, "Fuck United Health Insurance," in the way that we could say that, we'll say, "And fuck my aunt who did this." And I think that they're just not the same thing. I think if we understand power, if we understand the structure within oppression, then I'm going to view my tia very differently. I want people to view our family members very differently and have a lot more space for it. Because the book isn't like, "And so you should have wonderful relationships with everybody." Because right now, I haven't talked to my mom... I'm going on a year and a month. I'm perfectly okay with, "No. You need boundaries." And if people are harmful, they're harmful. And you can still learn a lot from them. You can still love them from afar. It's stripping us from the binary, I think that I'm trying to do. Because someone does something that's harmful, doesn't mean they're a bad person. So it's really claiming that, but with our families, that I am hoping people can have a more compassionate lens.

Propina

We’ll conclude our conversation with Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez next week. If you missed the first part of our conversation, you can find it here:

“Everybody should read it. But Latinas are the protagonists.”

For years before we officially launched La Cuenta, Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez has been a source of inspiration and guidance for our work. From founding Latina Rebels to her foundational 2021 book, For Brown Girls with Sharp Edges and Tender Hearts

Lastly, we know this past week has been a challenging one and is only a harbinger of atrocities to come. If you have a story or message you would like to convey to La Cuenta’s community, please get in touch.

We’ll see you next week.