“English Learner is what we do to kids. It's a label that we put on them, like a stamp.”

Exploring language learning and school systems with Dr. Ramón Antonio Martínez

Reflecting on the responsibilities of classroom teachers, Associate Professor Ramón Antonio Martínez spoke to how the “English learner” label can damage the lives of young people. In the final installment of our conversation with Dr. Martínez, he shares his insights from more than a decade of longitudinal research with youth in Los Angeles.

If you missed earlier installments of our conversation with Dr. Martínez, the first part covered his personal interests in language and the varied perspectives on multilingualism in America. We followed this up with a deeper exploration of the “English learner” label in U.S. schools. Today, we conclude our discussion exploring the specific intersection between the “English learner” label and individuals marked as undocumented in the U.S.

Alix Dick: Can you describe how your work on language policy intersects with the lives of people labeled undocumented?

Ramón Antonio Martínez: Yeah, for sure. Without going into too much detail, a lot of the kids that I've worked with have been undocumented or from mixed-status families.

Antero Garcia: When you say “mixed-status,” what does that mean?

RAM: Mixed-status just means that undocumented and documented people are in the same family. It could be where a parent is undocumented but the child is not or a parent and some of the children are undocumented but some of the children are US-born and are not undocumented.

I think there's a correlation [in research on language and undocumented communities]. A lot of children of immigrants or kids who are immigrants themselves come to this country for a better life. I won't say exact numbers, but at least half the kids that I work with are born in the United States of America, right, and they are in mixed-status families because their parents typically are undocumented. But they're born here. Being born here doesn't necessarily guarantee that you're going to have access to the same opportunities and advantages if you are in a mixed-status family, if your parents are undocumented.

AG: This is longitudinal research you’re talking about?

RAM: Yeah, this is a longitudinal study in Los Angeles. These kids are now 11th and 12th graders, and I started working with them when they were kindergartners and first graders. I've seen them grow up and get bigger. And each kid is unique and has a different trajectory. Some kids who are undocumented speak English better than they speak Spanish.

AD: Are there places where you’re seeing positive kinds of change?

RAM: I feel increasingly hopeful as I work with pre-service teachers. The teachers, the people that Antero and I work with in the teacher education program at Stanford - I feel like every year they become more radical, more hopeful. I am encouraged they're going to do right by kids or at least they want to.

I feel like my job is really just say [to teachers], “Don't be racist to kids.” My role is basically to explain that, yes, kids are learning language; here's some tools and strategies you can use. But I want you to rethink what you think you know about language and who these kids are. See them for who they are and let them teach you about who they are over time. Don't make assumptions. Don't start with the labels like “English learner.” That's not the beginning of the story of who these kids are. English learner is what we do to kids, is what school systems do to kids.

“English learner” is not the beginning of the story of who these kids are. English learner is what we do to kids, is what school systems do to kids.

AG: What do you mean by that?

RAM: Our preservice teachers come in thinking that being an “English learner” is a thing. That it's a type of student. And I want to disabuse them of that notion. I want them to understand that English learner isn't who kids are, English learner doesn't tell you anything about who kids are or even what they're learning. English learner is what we do to kids. It's a label that we put on them, like a stamp.

And kids are so much more than that. I show them examples of these kids that I've worked with through this longitudinal study. I show them videos just to demonstrate how amazing these kids are. That's basically my story to these teacher candidates: “Look how amazing these kids are. And now look at the label that diminishes them, that denigrates them, that underestimates them.” I want to show them the kids first. I want them to see these kids how I see them: as amazing kids.

Look how amazing these kids are. And now look at the label that diminishes them, that denigrates them, that underestimates them.

AD: That's the human side of things.

AG: The “English learner” label... It's funny. No one in this country goes around and says, "I'm documented." Right? It's a label we give to people, only in its absence.

AD: We only call someone undocumented if they're less than human. That is basically I think how we treat them.

AG: Yeah, I'm curious if the EL label operates in the same way.

RAM: Yeah. In linguistics we talk about markedness: what gets marked and what doesn't. Female gets marked, disabled gets marked, bilingual or multilingual get marked. What's unmarked is the norm. I think monolingualism is the unmarked norm. It's framed as the unmarked norm. But it's not the norm worldwide. Like I said, on Earth, it's not normal. And it's never actually been the norm in this country, but it's been framed as the norm to which we should aspire. Even our ideas about what constitutes fluency or proficiency in a language, it's all based on monolingual norms.

So, what's the best model of a proficient English speaker in the U.S.? It's someone who speaks it as their native language and who grew up speaking only one language. Supposedly. But actually, that's not normal. We have monolingual ideologies that govern how we think about what constitutes something like language proficiency or fluency. So yes, I think if undocumented is marked and othered and stigmatized, having documentation is the unmarked norm. And similarly, analogously like you suggested, speaking more than one language is marked and stigmatized and othered, and speaking only one language is the unmarked norm.

AG: You've brought up accents a couple time. And I'm curious how your work looks at if accents get marked. You've mentioned times when people-

RAM: I'm sorry, can you say that? I can't understand your accent. Can you say that again?

[laughs]

AG: Alix, you’ve said sometimes when you speak in Spanish and in English, people cannot figure out your accent or where you come from.

AD: Yeah, I feel like there is a stigma around some accents. When I speak English, people are like, "Where are you from?" Honestly, I don't know how to answer that question because I taught myself English. So, my accent comes from whatever I listened to, watched on TV, or heard how my friends pronounced things.

RAM: Yeah, accents are really interesting to me. Phonology as a branch of linguistics is super interesting. I love sound. That's part of my geeky interest in language, since the time I was a young child, it's been about the sounds of language. Being able to hear them and to reproduce them, I just geek out on that.

AG: I don't think I've told this to you, but I think this is a thing you do really well. You're really good at mimicking people's registers, you have a good ear for how people talk. Does that make sense?

RAM: Yeah, that's right. If I'm being Antero, “I think that's right.” You say that. [laughs]

I like that. But, look, I see a lot of kids doing that. They’re really skilled. They have an ear for language and they can reproduce it and do different accents. Stylistically, they have this linguistic dexterity where they can style-shift and sound like different people. I think that's really interesting and amazing. It's hard to do that. Just some of what we know based on research is that accent is the hardest thing to learn or the last thing to learn the older you get. The older you get, the harder it is.

Stylistically, [kids] have this linguistic dexterity where they can style-shift and sound like different people. I think that's really interesting and amazing.

And people have theorized for a long time about when is that age, that cut off? At what point does it get hard? Is your vocal tract--your vocal apparatus--less malleable, less flexible? There isn't a hard cut off point, but we do know that it gets harder. And oftentimes the last thing people perfect as they're acquiring a language is an accent. But the point is you don't need to acquire an accent in order to be fluent or proficient. Not all accents are considered equal or deemed equally unintelligible or intelligible. The point is we all have accents, right? Every one of us has an accent.

AG: Not me!

RAM: Everybody besides Antero in the world has an accent. Rosina Lippi-Green, who was a sociolinguist, has a book called English with an Accent. And there's a really beautiful dedication at the front. It says, "To my father, who had an accent I couldn't hear." And I love that. It makes me want to cry almost. It's so beautiful. But we all have accents, we all have accents. But we don't necessarily judge all accents equally. And there's some empirical research to suggest that people often see accents before they hear them.

Similarly, this overlaps with Jonathan [Rosa]'s work, which is more recent, which is this idea that we assume things about people based on racialized identity, that we see them and make assumptions about the kinds of speakers and the kinds of humans they are. So we all have accents, but not all accents are perceived equally. And like you said earlier, Alix, if you're poor and have an accent, it's “not fancy.”

Propina: Intergenerational Dreaming

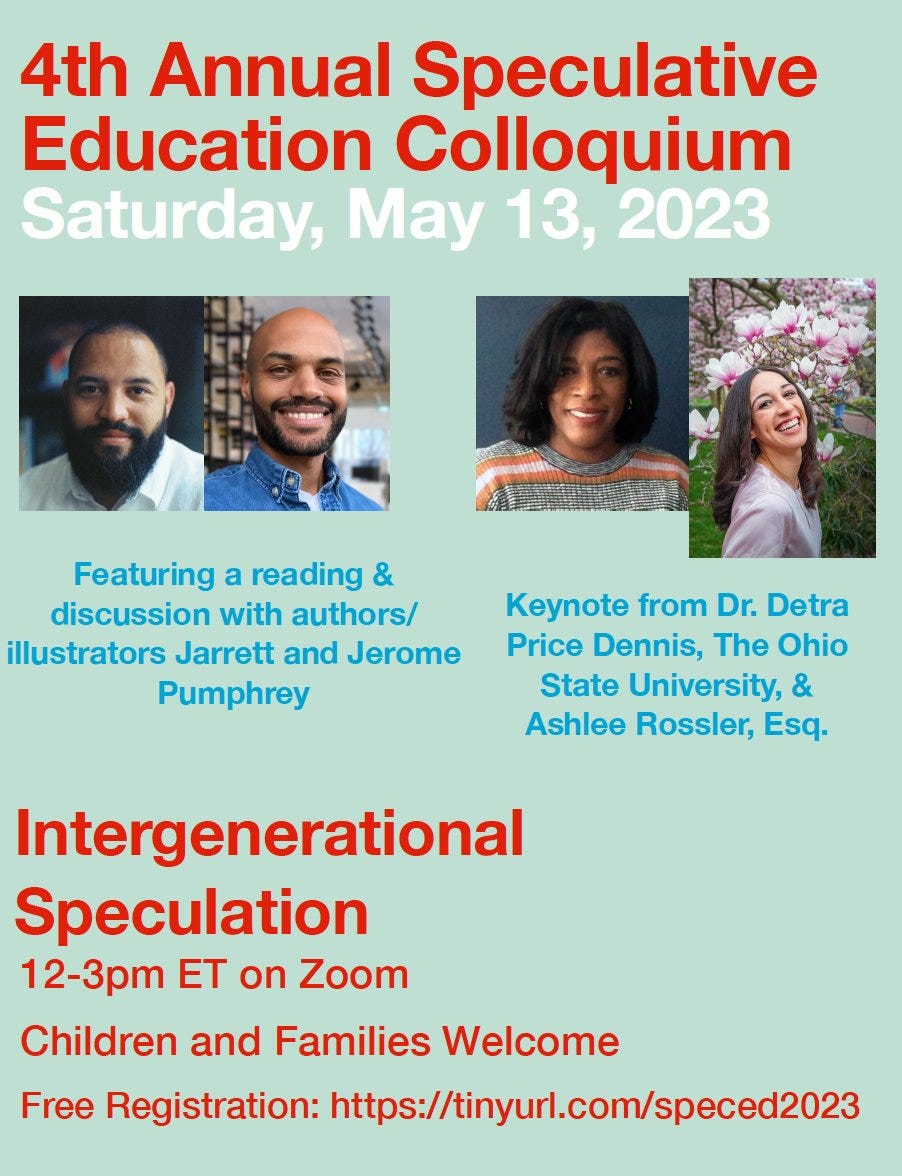

Something slightly different this week: If you’re reading this before Saturday, May 13, we invite you to join us for a free Speculative Education Colloquium.

Created by Antero and Dr. Nicole Mirra, the 4th annual SpecEd Colloquium features storytelling from two children’s authors, a keynote from a mother-daughter set of scholars, and an opportunity to dream of new worlds with other participants. Register here.

Though this convening isn’t specifically about immigration, it is about imagining and teaching for freer futures.

We’ll see you next week!