Art-Healing Praxis and Family Separation

Discussing immigration policies and family impact with Dr. Silvia Rodriguez Vega

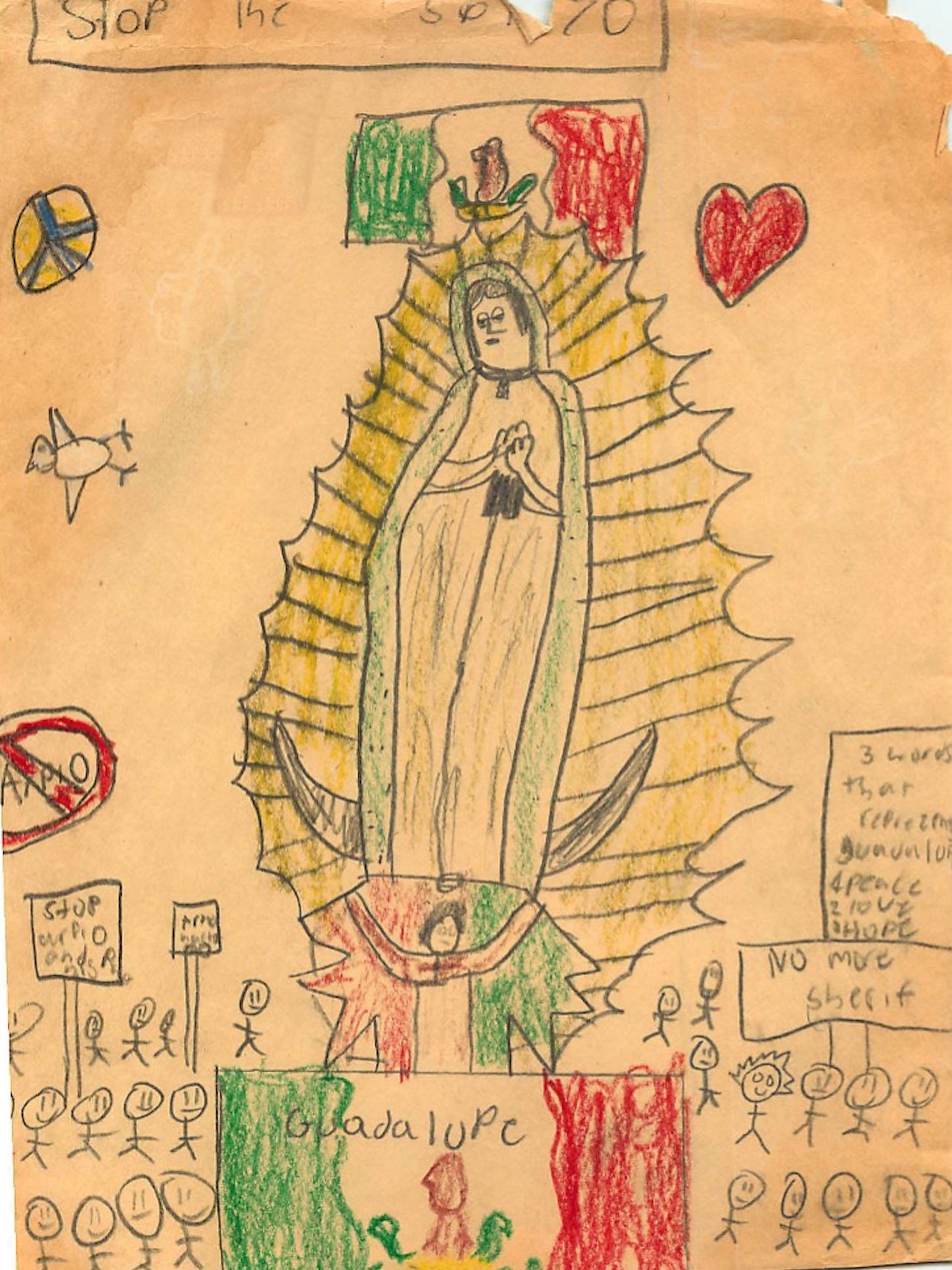

Flip through the pages of Drawing Deportation: Art and Resistance Among Immigrant Children and you see the lessons of immigration through the eyes of the most vulnerable individuals trying to survive in this country. A morose sun is crowded out by clouds and jail bars as a family peers out the window of their caged home, cut off from the world and nature. “Immigration is making everything fall apart,” one image declares.

Based on a decade of research in Arizona and California, Drawing Deportation is filled with images of play and imagination, loss and healing, pain and joy.

In this second part of our conversation, Dr. Silvia Rodriguez Vega, assistant professor in the Department of Chicana/o Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, discusses the key findings from her book and the impact of current immigration policies. If you missed the first part of this interview, check it out here, and stay tuned for the final part of our interview next week.

Antero Garcia: Your book articulates an “art-healing praxis.” Can you say what this means and what it might look like?

Silvia Rodriguez Vega: I am borrowing from Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and the idea of praxis and putting theory into practice. So, what does it mean to heal through art? I think that healing is such a huge word; it is sometimes used too easily. But a praxis of art and healing emphasizes the process of healing instead of a product. We can see the powerful products from the curriculum in all of the work I collected over the years in two different states. But what I believe is most powerful is the process that the children went through and their own personal development through the creation of art. To me, the cover [of Drawing Deportation] and the images in the book are extremely powerful and communicate important information. But what I found valuable was the ability of a child to communicate their feelings or fears or to process things through creating art. To me, that was the healing part.

AG: The change is the product.

SRV: Yeah, exactly. The praxis hopefully can lead to healing. Another way that I think about healing is being able to cope with something or being able to sit with it and process it. I feel that children are not even allowed to process feelings--especially when they do go through separation or a death, which I write about in the book. It becomes something so painful in the family that we try actively to not engage with it and ignore it. But when you're sitting with it and doing a drawing or creating an art piece, then you have the opportunity to imagine it and process it in your own time.

That's the healing and praxis part. It's not a matter of just giving our children a piece of paper and coloring materials. It’s taking them through a process of thinking critically about things, wondering why things have to be the way that they are, and discussing things that are important to us. All of that comes from Theatre of the Oppressed, which comes from Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Children are not even allowed to process feelings--especially when they do go through separation or a death ... It becomes something so painful in the family that we try actively to not engage with it and ignore it.

AG: I'm curious if you have advice or thoughts for parents and teachers who might be working in particularly vulnerable communities right now.

SRV: I'm definitely the first one to say that not anybody should take this curriculum or make their own and do this kind of work. Especially when we're dealing with a very vulnerable population who's experienced stress and PTSD and trauma. And at the same time, I feel that any opportunity to use creativity will be valuable. It doesn't have to be about the worst thing in your life like family separation. Kids were really eager to use art to talk about bullying and climate change and war and getting along and friendship. Anything that allows children to have creativity and space to process is valuable.

AG: Are there any specific activities that have been good entry-points for your work?

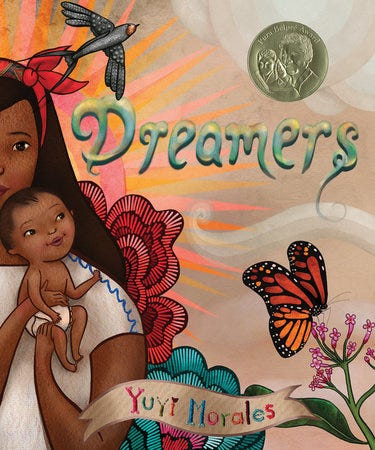

SRV: I often ask kids to watch the news and come back and tell me the most important news story they remember. Often, immigration will come up in that moment. From then on, students like to have a discussion and say, "Oh yeah, I saw that," or "I think this," and then I can ask follow-up questions: "What does it mean that this is happening?" Or "Who is that person?" And they'll give me their ideas. The other thing that comes to mind is the work of Sarah Rendón Garcia. She does work with parents and children and uses children's books to talk about immigration. She uses a book by Yuyi Morales called Dreamers.

AG: Oh, yeah. I know that book.

SRV: Yeah. It's a beautiful book, and it tells a story about [the author’s] immigration journey and having a child. Sarah Rendón Garcia will use that, and then she'll use a documentary by Jorge Ramos, Hate Rising, with kids talking about immigration. The kids are saying, "If Donald Trump builds a wall, I'm not going to see my grandma anymore." So kids start having a dialogue that’s based on the documentary paired with the children’s book.

AG: That's really cool. All of the research in your book was during Trump's administration?

SRV: No, it starts in Arizona during the Obama administration, 2008 to about 2012, and then it goes into the Trump era in California.

AG: I’m curious if the landscape of separation has changed or if you feel like the context is that different with Biden?

SRV: I think we knew that the Biden administration was going to be similar to the Obama era, because he was part of that administration. But what I think has really surprised immigration activists and folks that do immigration work is that Biden is actually very similar to Trump. The restrictions that he critiqued Trump for he is now executing himself. I think that is really telling and very unfortunate. So sadly, it doesn't feel like a lot has changed. Although the rhetoric is different and the narratives in the media are different, policy-wise, they are very similar.

Although the rhetoric is different and the narratives in the media are different, policy-wise [Biden and Trump] are very similar.

AG: I think people assume things are better because it’s not Trump. And that actually makes things worse: they're essentially the same as they were under Trump, but without as much attention on them anymore.

SRV: Yeah, I agree. It is worse, and I write in the book that the Obama administration created a blueprint that Trump took and ran with, but that doesn't take away from Obama being the “Deporter in Chief” and deporting more people than anybody before him.

AG: Biden might give him a run for his money by the end of his presidency.

SRV: Especially if you just think about asylum and that process. It was happening under Obama: I remember Hillary Clinton in her position said something like, "Don't come here," which is the same thing that Kamala Harris was saying. It goes to show that both political systems function in the same way. Their rhetoric is different, but equally dangerous.

Propina

If you are interested in exploring theater work similar to the approach in Drawing Deportation, Augusto Boal’s Games for Actors and Non-Actors is an accessible text for educators and organizers.

Mentioned above, you can stream Jorge Ramos’s Hate Rising:

We’ll see you next week as we conclude our interview with Silvia Rodriguez Vega.