All the art that I create is geared towards the immigrant and the undocumented experience.

Che Guerrero on humor, comedy, and survivor’s guilt while growing up undocumented in the U.S.

Through his humor and his level-headed explanations of immigration news, comedian and “artivist” Che Guerrero has been a source of reassurance and comfort for thousands in recent months. On TikTok and Instagram, Che’s voice has been vital in this moment, offering candid reflections on his own experiences growing up undocumented and bringing truth to power as he fights misinformation and racism.

In this first part of our conversation, Che describes how his work first began to center immigration under the first Trump administration. Che also reflects on the racist hierarchies shaping the comedy scene right now and the transformative experience of returning to the Dominican Republic for the first time.

ANTERO GARCIA: In your own words, can you describe what do you do?

CHE GUERRERO: I'm an artivist. I heard that word and I was like, "I like that a lot." I came to this country when I was six years old. I'm a visa overstay, and I grew up most of my life undocumented. I didn’t fully realize what being undocumented meant and the limitations that it put on my future until I became 18. I wanted to be a doctor, and I realized, "Ooh, I can't really go to medical school without papers and FAFSA and all stuff." So one of the ways to survive was I started being a standup comedian. I realized that clubs pay cash and they don't ask for papers. So I was like, "Perfect, great way to do this."

AG: When did you get started as a comedian?

CG: I started when I was 18, and it wasn't until the Trump administration, when I was 27, that I mentioned anything about being undocumented. I didn't let anybody know anything about my life in that way. But once I started seeing kids in cages, I started to realize like, "Oh my gosh, I could easily be one of those kids." That could have happened to me. So that's when I started really shifting everything that I do, standup, my writing, my poetry, everything, into being more of my personal experience growing up undocumented. I didn't realize how much people needed that. How it was going to resonate with people. Then the pandemic came.

So when I got on TikTok, because I had no way of getting up on stage and continuing with the message, I started using trending sounds to do humorous takes on what it's like when you're undocumented and you can't get a driver's license or you can't go to college, which is where [my previous online] name My Undocumented Ass came out of. Like, "Oh my undocumented ass couldn't go to college… " People liked that.

So, I started with that and that's where I realized that everything that I do, all the art that I create is all geared towards the immigrant and the undocumented experience. Then I started reporting on news stories and I realized that there's not a lot of journalistic integrity when it comes to TikTokers posting stuff. I hated the way that misinformation was being spread. Oddly, on the left... The right, totally horrible, but also on the left -- things that weren't quite true. I wanted to do a lot more research, and people have seemed to gravitate to the way that I do humor and reporting where I don't just say, “100,000 people are at the border.” I give historical context as to why it's happening.

I also add a lot of mixtures of humor so people can sort of digest it all in a way that they are able to get the information. So that's why I call it artivism.

I wanted to do a lot more research, and people have seemed to gravitate to the way that I do humor and reporting

AG: Going back to that very first time you’re seeing kids in cages, just some of the absolute worst images that we've seen, was deciding to start talking about your own immigration status a scary moment for you?

CG: Honestly, fear hasn't struck me till November 5th. Honestly, the fear just started. I have an upcoming performance, and I might call it my last immigration performance because I don't know if I'm going to freely be able to talk about these things once the new administration fully hits. But when I saw those kids in cages, what I felt more than fear was anger. I heard somebody say once, anger is good, if you can direct it to do good things. Just to be angry because you're stuck in traffic, you're just getting angry at everything now. But to be angry at a system and to be angry at the way you're seeing your people be treated, that's healthy anger. That's "I need to do something about this. I need to use whatever tools I have."

One thing I learned growing up was using comedy was a much easier way to speak to power. Like the old phrase, they can't kill you if they're laughing. So that's where I knew that I had the skill to get on stage and talk about immigration, the undocumented experience in a way that was digestible for people. What I didn't expect was the backlash that I got from the comedy community.

To be angry at a system and to be angry at the way you're seeing your people be treated, that's healthy anger.

AG: Can you describe this backlash?

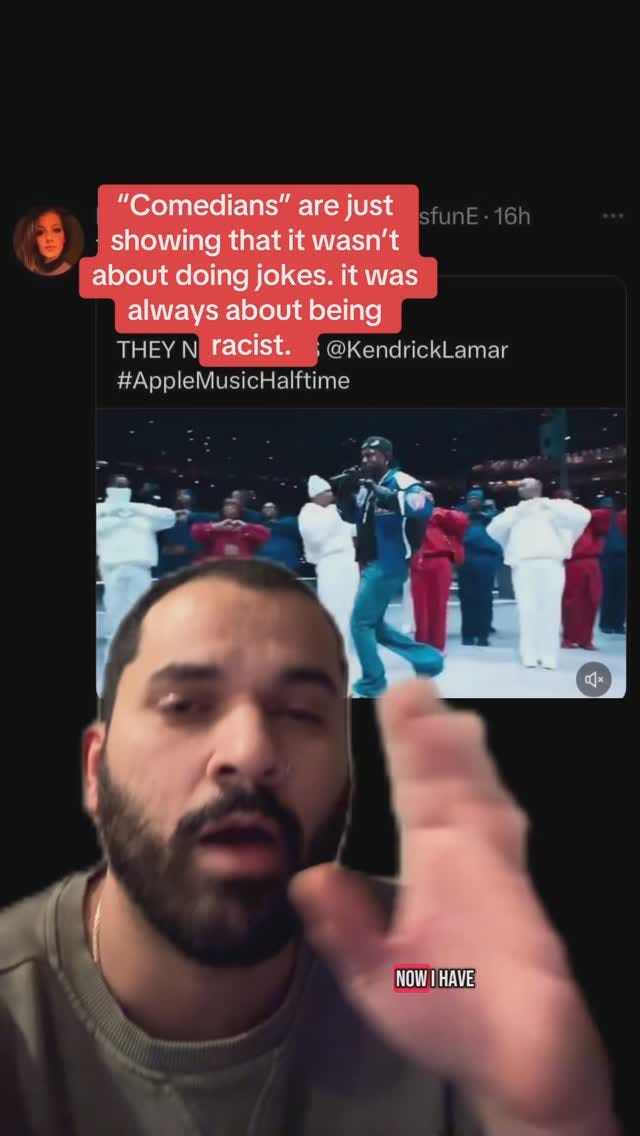

CG: The comedy community and comedy clubs aremostly dominated by white men and Trump supporters. I think of the three major comedy club chains, I know at least two of them are owned by Trump supporters.

AG: Whoa, really?

CG: Yes. I want to do a documentary about this. So the pipeline for a stand-up comedian who has the aspiration to be like a Kevin Hart goes through the comedy clubs. And, as I was saying, comedy clubs are consistently owned by white men who are Trump supporters. so I stopped getting booked. I started being blacklisted. I can show you my tax returns. I went from making $40,000 doing stand-up comedy to making $11,000 once I started talking about my immigration status.

Comedy clubs are consistently owned by white men who are Trump supporters. so I stopped getting booked. I started being blacklisted.

AG: Turns out being undocumented isn't great financially.

CG: Right, I actually did an open mic last night, and I was talking on stage. I was like, "I have a genuine fear of getting on stage because my humor is grounded in my undocumented experience." Any Joe Schmo in the audience could just call ICE on me.” White dudes are worried about getting cancelled for what they talk about. No, I'm going to get canceled, literally, if I talk about my experience. And somebody at the open mic raised their hand and said, "So stop talking about growing up undocumented," and it was an African-American dude. I was like, "Dude, that's like somebody telling you stop talking about being Black."

Stop talking about your major core life experience that has shaped the view of the world? That's where I was heartbroken at the fact that comedy is supposed to be free speech and you can say whatever you want. No, you can't. You have to play by these white supremacists' games if you want to make it to the place where you're on TV. So I started getting blackballed, blacklisted, whatever you want to call it. It's been very difficult for me to do stand-up comedy because comedy clubs rarely give me a night. Now they are because they see that I have a following, but it's not because I deserve it straight up on my merits.

AG: Given that context, are you making most of your income from your work on platforms like TikTok and Instagram?

CG: Yeah, it has become a source of income, but just since last September. I was actually pretty late to the game. I've learned to monetize my videos and things like that, and I'll be real, it's given me a lot of survivor's guilt.

AG: How so?

CG: A lot of people are suffering. I go on stage and I joke about not having a social or I joke about doing a lot of things that people are even terrified to speak about. So I really have a lot of survivor's guilt. I actually just went to Dominican Republic for the first time in 30 years.

AG: Oh wow.

CG: Yeah, over the Christmas break. I didn't let anybody know because of the place we live in now, I wasn't sure if somebody was going to report me or try to do something to not let me back in the country. So even that, I felt so guilty about being able to visit my home country, when I know millions of others don't have that luxury. I felt guilty the entire time. My fiance was like, "Look try and enjoy a little bit of this for yourself." I mean I'm not trying to be so heroic, but I'm like, "I don't feel like I'm free until all my people are free." So it's been a very hard thing.

On TikTok, when I report on news stories, if I ever report on a story where somebody has a GoFundMe, I take whatever money that video makes and I give a percentage of it to the GoFundMe to make sure that, "Hey, if this story went viral, this is your story, so I want to make sure that you are compensated properly for the story."

I felt so guilty about being able to visit my home country, when I know millions of others don't have that luxury. I felt guilty the entire time.

AG: I love that. I hear you on survivor's guilt, but congrats on being able to go back. I'm assuming you still have family in the Dominican Republic?

CG: Yeah, it was so trippy going back. It was so weird because I left when I was six, seven, so I eat cheese and I'm like, "I've eaten this cheese before." It's stuff that they don't have here. But it was also really weird to reconnect with roots that I didn't even know were there because my real last name [Che Guerrero is a stage name] holds weight in the Dominican Republic. I have family members who both worked for Trujillo, the worst dictator, and were part of the Mariposas movement that helped topple him.

AG: You had civil war at the dinner table!

CG: Yeah. It was like, absolutely so. My great-grandfather started one of the freest newspaper in the Dominican Republic. I didn't know that.

AG: Oh, wow. You weren't up on that at six years old? That's really disappointing.

[laughs]

CG: No, I didn't know. I guess because for people who grew up like I did in the US, you don't feel connected to this country because they constantly keep telling you, like, "You don't belong here. You aren't from here." And if you didn't grow up and you don't remember, it makes you feel very disconnected from the world, like you have no roots, no place that you can call your own.

So going back to DR was eye-opening in that sense of like, well, I do have a history. My family does have a place in this crazy world. But also I come to realize that if I had grown up in privilege, the way my family has down there, I might not have been the revolutionary I am today. You know?

So, it's a little bittersweet of being like, damn, growing up undocumented really showed me, when you grow up at the bottom, just how much they attack you, your being, everything that you are. Had I grown up in privilege, I wouldn't have been able to have seen that.

Propina

We’ll continue our conversation with Che next week. In addition to following him online, consider subscribing to his newsletter.

La Cuenta had its first pop-up over the weekend at the Last Saturdays night Market In Mesa, AZ. It was a wonderful evening and we are so grateful to Olga of Santa Sangre Tattoo and Last Saturdays for hosting our first pop-up! We are so grateful for everyone that stopped by and we hope to see you at the next one. (;

Here’s a little video for those who couldn’t make it.

We’ll see you next week.

Fantastic interview. Really captures the guilt and secrecy of being undocumented. My wife and my sister went through a lot of this. Also, super disappointing to hear about these comedy club owners, though I guess I shouldn't be surprised.