“A part of me feels very uncomfortable promoting my books right now, in a time when the events in them are so much more amplified.”

Julio Anta describes personal responsibilities as a writer under during the second Trump administration

In the first part of our conversation with writer, Julio Anta, he shared how seeing family separation during the first Trump administration compelled him to write. Now, in this final part of our interview, Julio reflects on the responsibilities he feels as a writer, witnessing a new—even harsher—round of atrocities under the Trump Administration.

ALIX DICK: What would you suggest as some first steps for aspiring writers?

JULIO ANTA: Short stories. That's how I started. When I started trying to learn how to be a writer, how to write comics, I kept running into the advice to start with mini comics. I started writing all of these four to 10 page comics that I would then hire artists to draw. And then I'd put them out for free online on Twitter and Instagram and my website. And these were all stories that were, again, from my point of view. So, my first story was about a Mexican American ICE agent that had spent his entire career going after human traffickers and trying to save children that had been kidnapped, which pre-Trump was a large part of what ICE did, but then found himself deporting his neighbors and people like him.

ANTERO GARCIA: Eerily prescient.

JA: And that was 2019. And then my next one was about a father that sought revenge on the cop that killed his son. So very much still the sort of thing that I write about, but in small bite-sized versions.

The benefit of writing short stories is that A, you can write them quickly, B, you can learn the lessons that there is to learn from writing a story quicker, and C, you can put it out to the world a lot easier and faster and see what people think.

Is there an appetite for the stories you want to read? If there is feedback, is it valid feedback? Because especially when you write work that is often politicized, there is going to be a lot of feedback. Some of it is not valid.

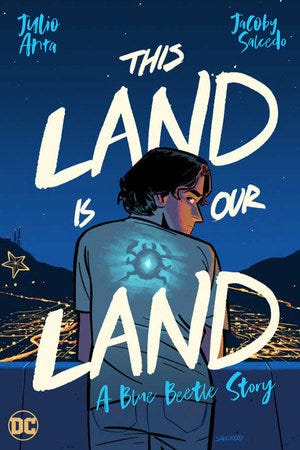

If you're trying to make comics, you can hire an artist to draw four to 10 pages, and that can be affordable to you and you can still make these comics and put them out. And it also is a sort of calling card for you. Editors might see it, other artists might see it. That's how I met Jacoby, who I've done multiple books with. I hired him to draw my second short story. And then all the lessons that I learned from there, I took them to Home, which was the whole reason I started trying to become a writer. So I think writing short stories is so important, and that's really the first step.

AG: I’m really resonating with the reasons you felt called to be a writer. We’re a few months into the second Trump administration and witnessing new atrocities by the day. How are you as a writer, as a parent, as a human being, thinking about your responsibilities right now?

JA: I was having a similar conversation with another author in November when we were both in Austin for the Texas Book Festival, and it was post-election. He was saying that he felt like he had to sort of fast-track a book that he wasn't going to write until later that focuses on these issues because of the incoming Trump presidency.

For me, I don't know, it's tough. Putting the work aside, it's deja vu, but it's deja vu to the extreme where it feels like the first time around, there was general outrage, right? But this time, I think we all saw business, institutions sort of capitulate in advance and all sort of normalized Trump post-election before he was even inaugurated. And I think those of us who are in opposition to him, a lot of us are exhausted already, which is the point. And the things that he's doing are even worse so far.

If you think about what he had done in the first weeks of his first term compared to what he's done now, we already have Guantanamo being turned into a 30,000-bed migrant prison, detention center.

As is always the issue with Trump, it's hard to tell what is legal and what will be challenged and not actually happen. It's tough. I'm involved in some local advocacy groups, so I am doing on-the-ground work here that I don't really talk about a lot of times.

I'm wrestling with the idea that I write these books--I wrote Home and Frontera and This Land is Our Land--which talk about these issues because I think they're important and because I want people to read them. So there's a part of me that feels like this is the time you should be talking about them and getting the word out. But another part of me, which is the part that's dominating my feelings right now, feels very uncomfortable with promoting my books right now, in a time when the events of my books are so much more amplified.

I think it's also important to remember that deportations didn't stop under Biden. The targeting of undocumented and Latinos and black people that are from other countries didn't stop under Biden. Obama is still the president most responsible for the most deportations. But I think the difference is that there was a semblance that this is the law, we can fight what the laws that are on the books. It felt like less of an outward hatred of our neighbors and our families and our communities than we're seeing now.

“I think it's also important to remember that deportations didn't stop under Biden …But I think the difference is that it felt like less of an outward hatred of our neighbors and our families and our communities than we're seeing now.”

AG: La Cuenta is named after the idea of the invisible costs incurred by individuals who are labeled undocumented in this country. From your writing and from your own experiences with your family, if you could imagine a bill that we could give to U.S. government for the hidden costs of the undocumented community, what you would put on that bill?

JA: The first thing that comes to mind is separation, the separation of families. And I'm not talking about family separation in 2018, I'm talking generally. I mentioned earlier thatmy father is from Cuba. He came to the U.S. in '62 when he was five years old. And I think the great story of the Cuban diaspora is one of family separation. I was in Cuba the summer before last, and when you go there and you talk to people, every single person knows someone that has left--especially recently when over a 100,000 people left in 2023.

Obviously, it is not just about Cuba. It’s any person that is related to someone that has left their country. And for undocumented people, it makes it more difficult because they can't go back unless they want to risk crossing the border again. Before the border was militarized, there were people that would go to the U.S. for the season to work a certain crop and then they'd go back home to their family for the rest of the year in Mexico. And that was just a regular pattern of human labor migration. People in the U.S. knew that and that was accepted. It wasn't politicized the way that it is now.

And for example, my family in Colombia, my mother was born in the U.S. She would be a so-called anchor baby, birthright citizenship receiver. Both of her parents were undocumented. I have very little relationship with my family in Colombia because of that separation. By the time I was born, my grandparents had their papers, but because of the financial costs, I never went to Colombia until I was 18. So I don't have that relationship with that side of my family. Those are more distant relatives, but imagine if that was my mother or my grandparents or marriages that are separated across borders. To me, the emotional cost of separation is the biggest one and the one that I think needs to be talked about. It is about the way that these artificial borders and the economics of living in this country forbid people from seeing their loved ones as often as they'd like.

Propina

We want to thank Julio Anta for his time sharing his work with us. If you missed the first parts of our conversation, you can find them here:

If you need know-your-rights stickers, let us know where to mail you some.

We’ll see you next week.